By Alyn Griffiths

Peter Behrens is considered by many to be the world’s first true industrial designer. As artistic director of German manufacturing firm AEG between 1907 and 1914, he was one of the first to apply his artistic training to the design of cutting-edge technology, and became responsible for everything from the company logotype to light fixtures, furniture, clothes and cutlery. He also designed great buildings for industry, including the pioneering proto-Modernist AEG Turbine Hall in Berlin (1908-09).

Behrens’ residential architecture is less well known but it similarly reflects his visionary approach, which evolved to encompass various styles, such as Jugendstil, Brick Expressionism and an early form of Modernism known as New Objectivity. With their simple forms and expert craftsmanship, his houses embody the principles of functionalism and the unification of creative disciplines that came to be central to the Bauhaus school, founded in 1919 by one of his protégés, Walter Gropius.

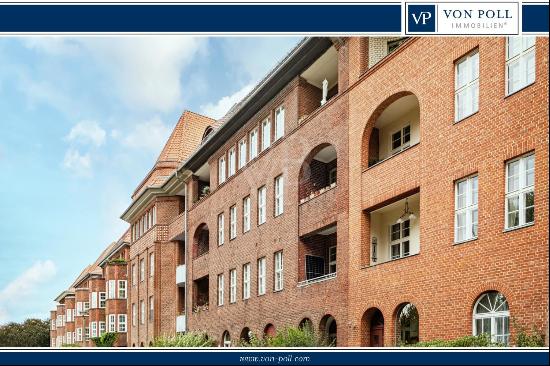

This five-bedroom house in the Berlin suburb of Schlachtensee — currently on the market for €5.2mn — was designed by Behrens for the psychologist Kurt Lewin and his wife Gertrud Weiss Lewin between 1929 and 1930. It is an example of how rationalist architecture, with its foundations in reason, logic and science, can be used to create a comfortable home, and shows Behrens’ ability to transfer his radically modern philosophy to every aspect of a project — from the bold, geometric forms, such as the semi-circular window overlooking the street, to the bright white interior with its subtle industrial details, such as the modern metal door handles. This approach, known as a “gesamtkunstwerk” or total work of art, would later be adopted by several of the architect’s disciples, including Gropius, Adolf Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, all of whom trained at his office in Neubabelsberg.

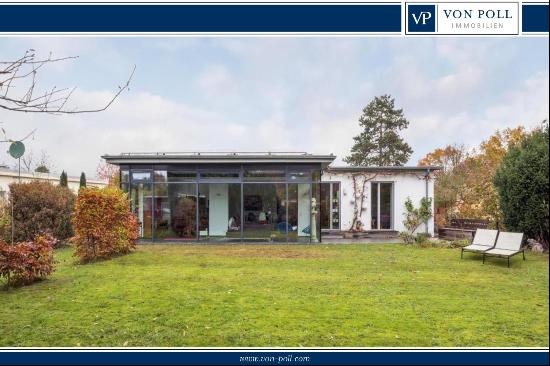

The villa consists of several asymmetrically arranged blocks that exploit the sloping site and allow for a lower entrance to the single-storey apartment and double garage that adjoins the main house. The exterior — which is defined by flush steel windows and a flat roof, as well as a connecting garden and roof terraces — is typical of the New Objectivity movement and the Lewins wanted the house’s interior to reflect the modernity of the outside.

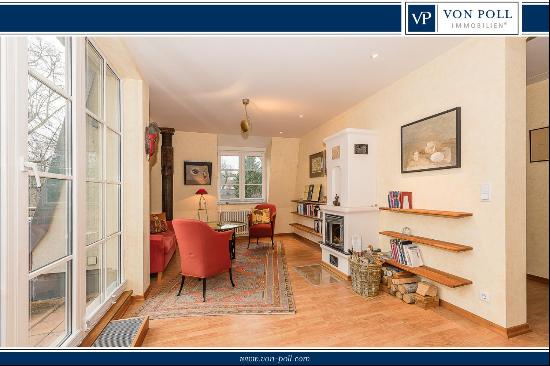

Following disagreements with Behrens, the couple engaged the renowned Bauhaus architect and designer Marcel Breuer to oversee the works. Breuer responded to the straightforward floor plan by creating bespoke built-in cabinetry and introducing examples of his trademark bent-steel furniture, including the unusual wavy coat rail at the entrance.

According to Adrian Ochse, a member of the family selling the house, whose wife grew up there, every aspect of the building was meticulously designed around the lifestyles of its occupants: “The house was planned down to the last detail, from the window handles to the heated garage and a moth-proof wardrobe for fur coats. [It is a] spirit that can be felt in every part of the house.”

In addition to its architectural significance, the property has a remarkable history. In 1933, the Lewins, who were Jewish, were forced to emigrate to the US and the house was sold to another family, the Wistens, who provided refuge for persecuted Jews there during the Nazi period.

Subsequent generations of the Wistens have taken care over the intervening years to preserve its bright, airy and modern aesthetic and now, almost a century on from its completion, the family is keen to pass the house on to another conscientious owner. Though it is in need of some restoration, the building still feels strikingly contemporary. Most of the original features — such as the walnut parquet floors, ceiling lamps and a solid-wood library in the study — remain, making this an exemplary case study of Modernist residential architecture.

Photography: Koch & Friends Immobilien