By Tom Owen

A disused fishmeal storage shed may seem an unlikely dream home. Yet, in John Steinbeck’s classic 1945 novel Cannery Row it becomes a symbol of community and fellowship and shows that “home” means far more than just a building or geographical location. The place in this case is a dockside in Monterey, California, also the setting for sequel book Sweet Thursday, and the earlier Tortilla Flat.

Cannery Row, which was filmed in 1982, starts with the acquisition of an old warehouse by a group of vagrants. Their leader, Mack makes a bargain with the owner, Lee Chong, offering to live in the warehouse with the rest of the boys in return for keeping it safe from smashed windows and other catastrophes that might befall it. They settle on a nominal sum of $5 per month in rent, both sides safe in the knowledge that none will ever be paid. Mack is happy that he has a place to sleep, and Lee is happy that his warehouse will remain intact. The new home gets dubbed “The Palace Flophouse & Grill”, and the nickname sticks.

At first the large storage space is bare and unfurnished. Mack and the boys sleep in chalk-painted rectangles on the exposed floorboards — each man’s space is his own. So far, so unappealing. One rainy day though, Hughie digs up an old military cot from somewhere. “That night the others lying on the floor in their squares watched Hughie ooze gracefully into his cot — they heard him sigh with abysmal comfort and he was asleep and snoring before anyone else.”

Suddenly Mack and the other boys are all over town purloining furniture. They also get hold of some red paint to make their new acquisitions less recognisable should the original owners ever come by the Palace. “The boys outdid one another in beautifying the Palace Flophouse until after a few months it was, if anything, overfurnished. There were old carpets on the floor, chairs with and without seats. Mack had a wicker chaise longue painted bright red. There were tables, a grandfather clock without dial, face or works. The walls were whitewashed which made it almost light and airy.”

This sums up Mack and the boys’ attitude. They will go to great lengths to avoid work, but invest huge energy into a good scheme. In their worldview, there is nothing so dishonest as earning an honest living. With the Palace properly furnished, Mack and the boys spend the rest of the novel thinking up ways of scraping together enough money to buy a communal pint of whisky, or — in the big set-piece ending — to put on a party for their friend, the unofficial mayor of Cannery Row, known only as Doc.

I long to join them in spending all day looking out over the busy workings of the fishery and canning wharf (although these days the real Cannery Row in Monterey is much more genteel and tourist-orientated) and pass quiet judgment on the goings-on. At night I want to retire to some esoteric but well-used and deeply comfortable piece of furniture to sleep. Mostly I just want to be one of the guys — and if someone happens to have a dash of whisky, then all the better.

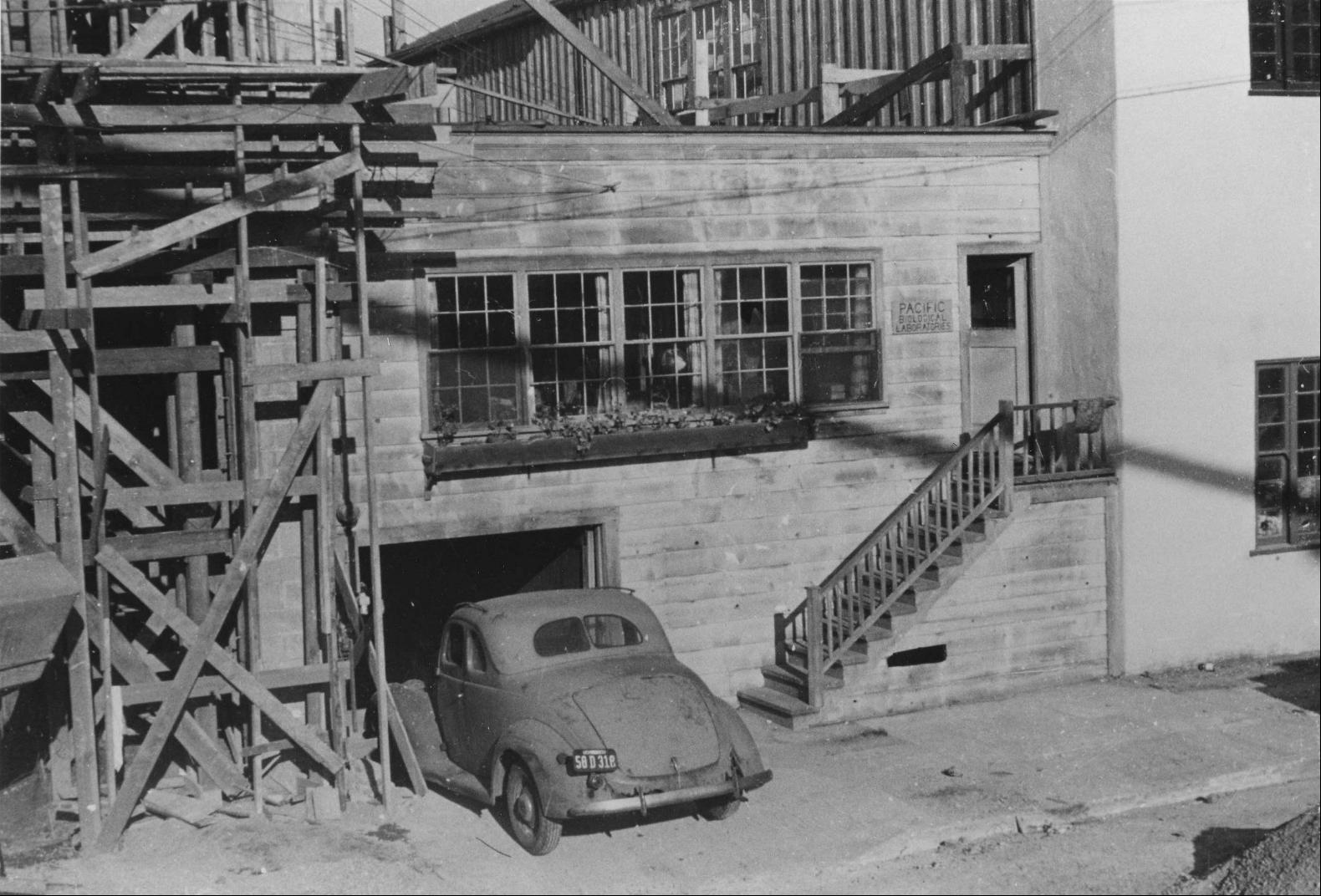

Photography: MGM/Michael Philips/Kobal/Shutterstock