By Anna Winston

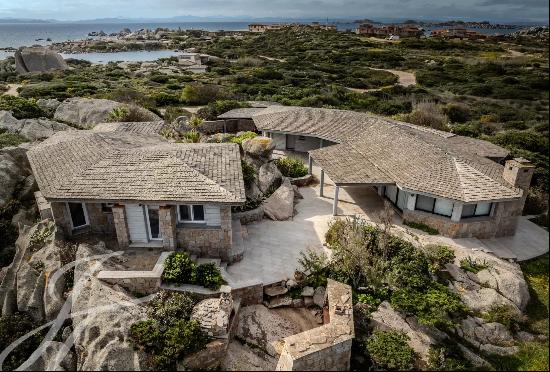

There is an extraordinary house on the tiny island of Cavallo, off the southern tip of Corsica, but you have to look pretty hard to find it. Nestled in the rocky shore, it is almost invisible from the land: terraces are shaded by wooden awnings that appear to have washed up on the beach. Inside, white sculptural forms give the impression that you are in a cave, where generous openings frame the view out to sea, across a small private beach.

Even on an island known for luxury villas, this house, on the market for €9.9mn, is something special. The five-bedroom family home was designed by the French architect Savin Couelle and sits among vast hunks of granite on a one-hectare peninsula, within sight of Sardinia. Built in 1990, it is an important example of Couelle’s work, which combines organic forms with a neutral palette of raw, natural materials and splashes of colour from the surrounding landscape.

“I was lucky enough to accompany my father to Cavallo at the very beginning of the [project],” says Alexandre, Savin’s son, who is also an architect. “He explained to me that this house would be like an outpost nestled between these great rocky masses. He imagined the winter storms assaulting the house; he was looking for that exchange between the elements; the wind, the waves and the spray. This house . . . has no equivalent in his work.”

Couelle first arrived in Sardinia in the 1960s with his father, the architect Jacques Couelle, who was commissioned to create the Cala di Volpe hotel, one of the key developments in the Aga Khan’s transformation of the Sardinian coast. Renamed the Costa Smeralda, the coast became one of the most desirable — and expensive — destinations in Europe.

The Aga Khan gathered together architects who shared an interest in using local materials to design structures that were closely connected to their surroundings. The designers were invited to create key public buildings and spaces, as well as tourist destinations. Collectively, they ushered in a style that was simultaneously rooted in the local environment and sympathetic to the needs and sensibilities of a cultured, international audience.

Savin later settled in the area and became one of the most popular local architects, designing private villas along the coast of Sardinia and Corsica. He was instrumental in defining not just the aesthetic of Corsican and Sardinian architecture but an entire branch of Mediterranean Modernism, and his work was often copied and imitated — something he enjoyed, according to his son.

Savin was a completist who cultivated relationships with local craftspeople who became the “hands” of the architect, allowing him to refine the tiniest details of each design — from the handles on the doors to the shape of each stone in a paved floor.

“Each project had to respect the history [of the area] by retaining the local traditions; each had to tell a story and have a unique personality,” says Alexandre. “It is difficult to classify his [Savin’s] architecture, but it certainly comes close to the work of a sculptor in its search for perfect composition. The apparent complexity of the forms, the different materials and the play of light are staged and orchestrated to make each of his creations unique.”

Photography: Corsica Sotheby's International Realty