By Edwin Heathcote

The coronavirus lockdown has hit those people who live in apartments hard. While those in the country may have access to nature, those in the suburbs probably have gardens and the wealthy might even have second homes, in the centre of the city the best many can often hope for is a balcony.

It is, perhaps, the most theatrical element in domestic architecture, a ledge which turns the city streets into a theatre, transforming the apartment from a cage into a royal box with the simple gesture of opening a double door. In recent times the nature of this theatricality became apparent when residents in Italy, Spain and France, confined for long days to their often small apartments, emerged in the evenings to serenade each other, join in musical jams or applaud health workers.

Suddenly, the city’s balconies conjoined to become an auditorium, bringing life to deserted streets and squares, making the city alive again while everything remained empty below. These private spaces became suddenly public, platforms for civic expression.

It was a remarkable, life-affirming sight and one which confirms the potential importance of the balcony not only to the apartment but to the broader city, its context and its culture.

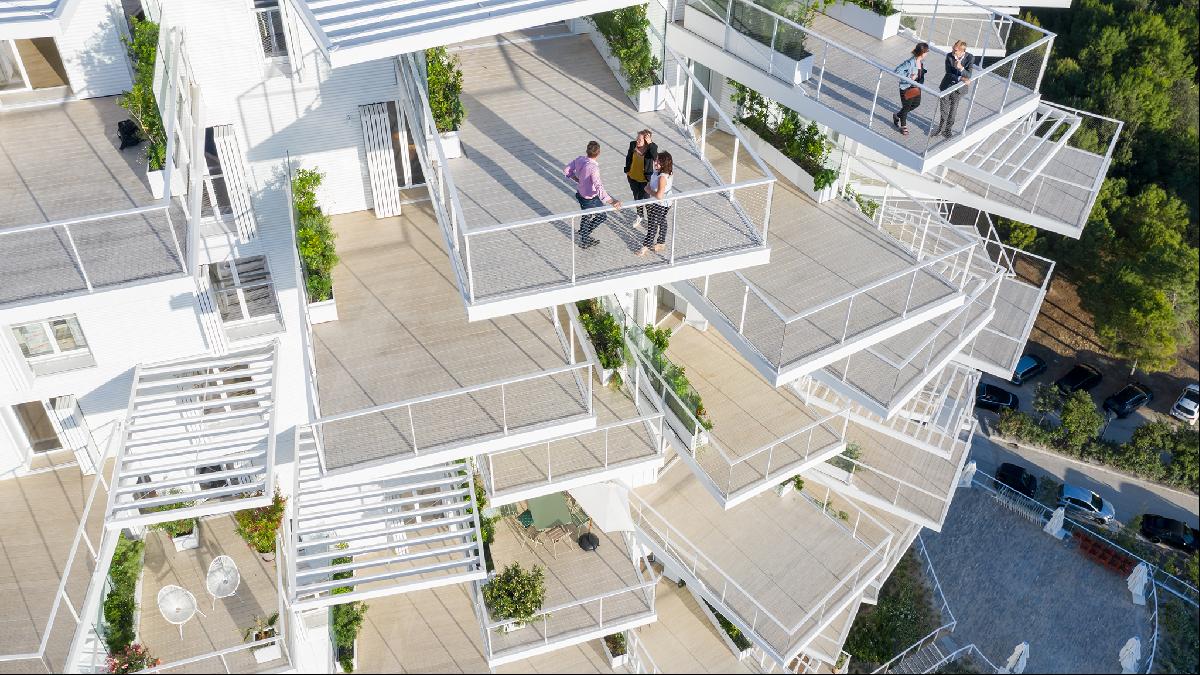

After decades of smooth glass towers or mean little boxy balconies, which end up being used as bicycle and baby toy storage, big balconies have recently emerged not only as an amenity but as the defining characteristic of an emerging architecture. Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto’s L'Arbre Blanc tower in Montpellier, France, is a balcony building, a tower studded with protruding platforms like some strange version of my favourite childhood game Kerplunk, with cocktail sticks replaced by playing cards.

The balconies are huge, some cantilevering seven metres from the face of the building, and are conceived as full-sized external rooms. On the upper stories projecting brises-soleil sprout out above them to provide shade from the sun.

Sou Fujimoto is also working on another French balcony bonanza (along with Nicolas Laisné and Dimitri Roussel, who also collaborated on the Montpellier tower), this time in Nice. The Méridia Tower is the most distinctive moment in a larger project and it is reminiscent of mid-century Miami modernism, which was exemplified by architect Morris Lapidus with its canopies and cheese-hole cut outs. The balconies, which wrap all the way around the tower, become more extravagant in plan as they rise, creating an increasingly sculptural profile, flaring out in ever wackier plan forms.

Some might argue that this is a cheap way to create a recognisable architecture, building a slab block and surrounding it with frills. They might be right, but in a warming climate it is difficult to argue it does not make sense. The only difficulty is coherence; if every architect were to indulge in this kind of design the result would be a mess.

It seems to increasingly be a particularly French phenomenon, even if its architects may be from elsewhere. Beijing-based MAD Architects, for instance, recently completed the UNIC tower on a former railway yard overlooking the Martin Luther King Park in Paris. The undulating wraparound balconies create a serpentine, wavy footprint.

Showing a little more control and urbanity, architects Brisac Gonzalez have just launched a much more restrained complex that is equally defined by its balconies. Shifted and staggered in relation to the tower they emerge from, the outdoor spaces of the O4A mixed use development in Paris create an elegant identity for a new neighbourhood. The mixed-use development includes a school, sports hall and community facilities as well as social housing and the identity is clearly defined by the balconies.

But here they are presented as a more communal affair, uniting the buildings in the complex in a shared language. All the architects of the various blocks have settled on a language of continuous balconies, which gives a coherent aesthetic to the development. Brisac Gonzalez’s simple moves, like the diamond grid balcony fronts on the practice’s building, create a distinctive, elegant appearance without veering too far into self-conscious branding.

More controlled still is Paris-based Renzo Piano’s Eighty Seven Park at Miami Beach (with admirably restrained interiors by another Paris-based practice, RDAI). The capsule-shaped plan is ringed by a stack of delicate, uniform balconies which give it a distinctive, streamlined profile, very self-contained and a bit of a relief from some of the more acrobatic Miami towers.

The balcony has travelled a path from a minor, sculptural addition to a window to becoming, in effect, the architecture itself. It has been a remarkable transformation for an architectural element that was once a minor appendage, popularised in Baron Haussmann’s Paris as a hybrid of function and wrought-iron decoration on the façades of the city’s new apartment blocks.

Perhaps it is to do with the desire to connect the interior with the exterior, the public with the private, the apartment with the fresh air and the sky. Perhaps it has become an affordable way of giving expression to a formless and cheap building, a mask for generic anonymity. Or perhaps it is a second skin that allows architects to exercise their desires for form-making while still claiming economy and lightness for their structures.

Either way, it looks like the wraparound, stack-up, stick out and wavy balcony is fast becoming an unavoidable feature of the contemporary skyline.

Photographs: Getty Images