By Edwin Heathcote

I recently came across some photographs of the most remarkable fireplace. Hans Demarmels’ Rebberg House of 1965 is fiercely Brutalist, a sculptural tour de force built with a conviction and sense of shape and form more usually reserved for public buildings — an art gallery or a town hall perhaps. But Demarmels condensed the power of brutalist concrete into a domestic fireplace. It is true he added a little Constructivism, perhaps a bit of De Stijl and maybe even a touch of Frank Lloyd Wright and Japanese Metabolism, and from these ingredients cooked up this centrepiece like no other.

This is the time of year when those of us in the northern hemisphere think about gathering around a fireplace, even people like me who live in 1960s houses with not even a semblance of a chimney. For most of the history of modernism the fireplace has been relegated to a curiosity. Rendered irrelevant by central heating, it became an anachronism but yet one which tenaciously survived.

Our yearning for fire is deep seated; the flames give symbolic as well as physical warmth and succour, and the fireplace becomes the focal point of an interior. With winter setting in and no real appetite to go out (never more so than now), the fire becomes a strange attractor, a visceral image of warmth.

Some architects never abandoned the fireplace, seeing it not as something obsolete but something physically and psychologically critical to the condition of dwelling. Frank Lloyd Wright’s fireplaces, such as the huge, constructivist sculpture of Hollyhock House (main picture, above) in Los Angeles (1921), were the absolute anchors of the architecture, set at the heart of the home.

There are some curious pieces. I was struck by the fireplace in Alvar Aalto’s Helsinki home (1936), a modest brick construction, which has a steep wooden stair rising from it and pleasantly warmed brick steps to its left.

Rudolph Schindler seems to have imported some of his central European instincts to California in the house he built in 1922 (the West Coast’s first real modernist dwelling). With its eccentric mix of Japanese-inflected sliding walls, Viennese nooks and Frank Lloyd Wright-influenced plan its fireplaces are austere yet their language of copper and concrete, darkness and simple surface is pivotal to the character of the rooms. Even the garden has a fireplace.

Schindler’s Viennese contemporary Richard Neutra also always made sure to add a fireplace to his houses, no matter how otherwise modern. His signature was a floating seating platform, a ledge which could double as a seat but which also leavened the appearance of the fireplace, making it as apparently lightweight as the architecture.

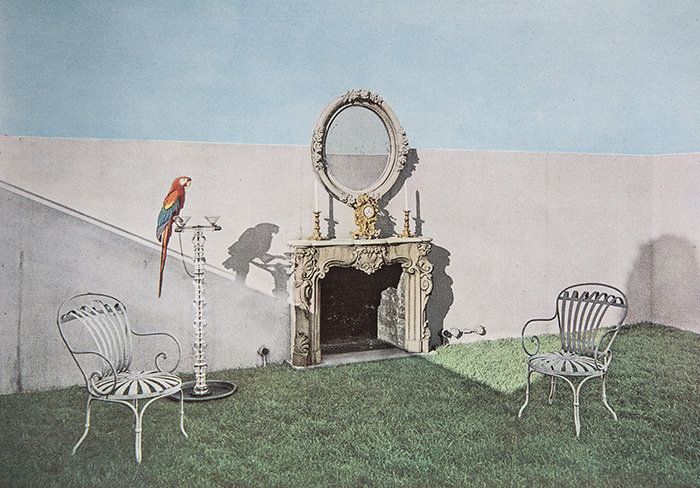

Something of Schindler’s elemental language is there in the interiors of Luis Barragán, albeit alleviated by vivid colour. The fireplace sits as an independent element, an architecture within the architecture. Le Corbusier did something similar in his otherwise sparse Maisons Jaoul in Neuilly-sur-Seine (1954-56) but his best use of a fireplace was in the unlikely setting of the rooftop of an apartment on the Champs-Élysées that he designed for art collector and interior decorator Charlie de Beistegui in 1929. I suspect Beistegui might have had more to do with it though than Le Corbusier. Here, an ornate, Rococo fireplace was inserted on to a modernist white terrace. Crowned with a gilded mirror, a pair of ormolu candlesticks and a stand for a macaw, the absurdity was precisely embodied in the way in which a fireplace so powerfully suggests an interior, even in the absence of walls and with the sky for a roof.

Philip Johnson’s Glass House, his retreat in New Canaan, Connecticut (1949), was an utterly ethereal thing, an insubstantial glass box, which outdid his idol Mies van der Rohe, whose own glass box, the Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois, was completed in 1951. Its one solid element is the brick cylinder of the fireplace (with the toilet behind it), a moment which anchors the building in the earthy material of the landscape. In its way it is more successful than Mies’s version, which sits slightly uncomfortably beneath the cupboards. It is an assertion that the place of the fireplace was assured in even the most determinedly lightweight of modernist architecture.

No one, perhaps, went more overboard with fireplaces than Bruce Goff, who worked for Wright but left to carve his own unique niche. The pink-tiled fireplace with a window behind and a chunky iron stove inside, which he designed for the bizarre cylindrical Al Struckus House in Woodland Hills, Los Angeles, at the start of the 1980s, is something else.

Goff’s other obsession was the circular conversation pit with a stove at its centre. His Adams House in Vinita, Oklahoma (1961) and the Eddie Parker residence — or the Round House — in Dallas, Texas, designed together with his protégé, Parker, in 1962, both feature stoves with flues that rise up through an opening in the roof, yurt-like.

And as we are on elemental, the architecture practice with that name designed a house in Los Vilos, Chile: the Ocho Quebradas House (2019). The striking concrete design is centred around a hole in the courtyard that functions not only as fulcrum but as a fire pit. Above it, the concrete roof is open to the sky, forming a simple chimney.

For its Chalet Forestier in Quebec, Atelier Barda expanded the influence of the fireplace across an entire wall. The stacked logs, redolent of the landscape outside, become the finish as the functions of the fireplace expand into the architecture.

At a house overlooking Lake Maggiore in Switzerland, Wespi de Meuron Romeo architects use the fireplace to turn the corner between the epic view and an intimate courtyard, its glow suggesting both the elemental and the intimate.

The rebirth of fireplaces in contemporary houses suggests something was missing: the sense of a centre. If the fireplace is often the focus of a contemporary room it is no accident. The word focus derives from the Latin for hearth or fireplace. Paying tribute to Vesta, the goddess of the hearth and the home itself, Romans would place votive objects and effigies around the fire. We might already be cladding ours in wreaths and candles.

The fireplace was the linguistic, physical and psychological centre of the house. And now no matter what new heating technologies emerge, it looks like it always might be.

Check out five of the best homes with fantastic fireplaces for sale on FT Property Listings here.

Looking for tips on how to style your existing fireplace? Our product round-up features furnishings to help make it a cosy centrepiece.

Photographs: Joshua White; Hans Demarmels Archive; Pinja Eerola/Alvar Aalto Foundation; FLC/Dacs; CaixaForum Madrid/La Caixa Foundation; Randy Duchaine/Alamy