By Joanna Walsh

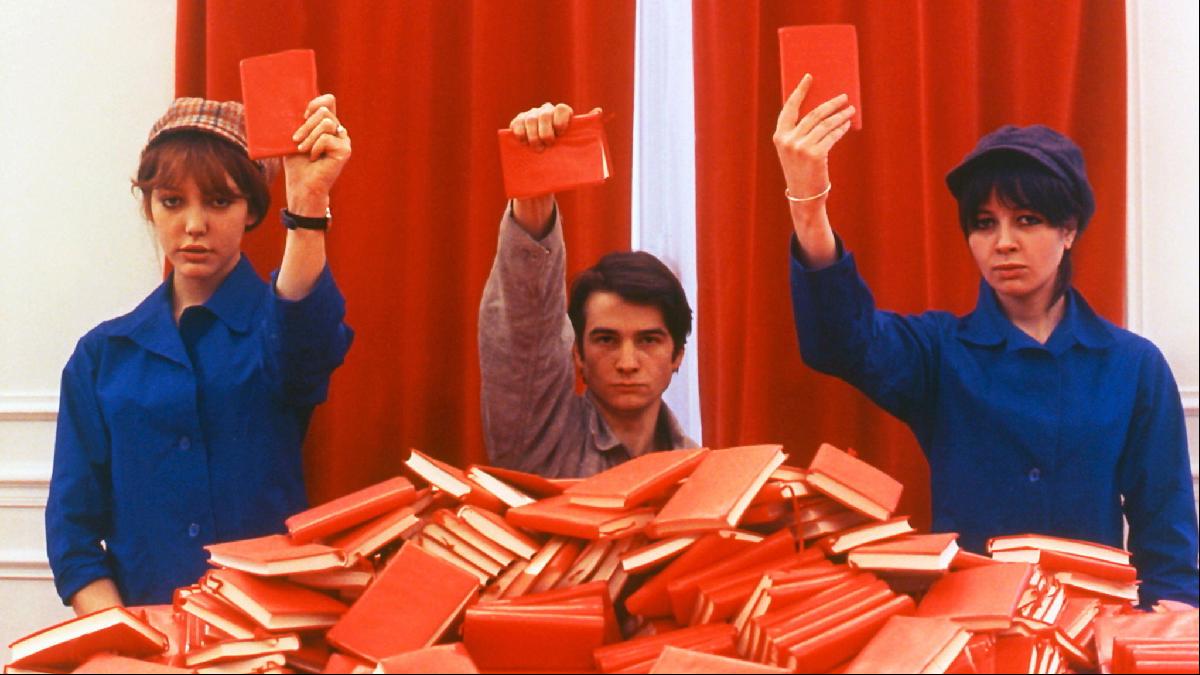

I long wanted to live in a French New Wave apartment, a place where the interior design reflects radical new approaches to living. In Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 film La Chinoise, a group of young idealists set up a commune in a Paris flat. The white walls are a work in progress, painted with rough squares of primary colours and the odd political slogan: “Il faut confronter des idées vagues avec des images claires” (Vague ideas must be confronted with clear images).

Nothing could be clearer than Godard’s sense of interior design. In his 1961 film, Une femme est une femme, for example, there are blank walls and a few carefully chosen brocante (flea market) finds, everyday objects made beautiful by their stark context: a blue enamel teapot, a red lampshade, a butter-yellow tea towel. In Godard’s work — above all in La Chinoise, which is dominated by Maoist red — colour carries meaning. When asked by the magazine Les Cahiers de Cinema why there was so much blood in his 1965 film Pierrot le Fou, Godard answered, “It’s not blood, it’s red.”

Godard’s interiors recall those of other French New Wave directors: the gilt-frame-baroque-on-white-wall minimalism of drag queen Gabriel and his costumier wife Albertine’s apartment in Louis Malle’s Zazie dans le Metro (1960), or the dream Parisian concierge apartment in Agnès Varda’s Cléo de 5 à 7 (1962), everything whitewashed to show off Cléo’s darkwood barley twist four-poster and Ottoman rugs, not to mention her piano and trapeze swing.

At the end of La Chinoise, the revolutionaries are gone and two bourgeoises arrive to pick up the pieces (“Maman will be furious!” “I hope they’ve not done anything to the interior.”). It turns out the cell had borrowed the apartment from rich relatives, their radicalism at least partially a holiday romance.

This was not the case for Godard, who lived in the apartment where the movie was filmed and post-La Chinoise, gave up his auteur status to work with a film co-op. He and his wife, the movie’s star, Anne Wiazemsky, rented, not owned, and though they both came from the highest of haute bourgeoisie, their political commitments were more complex, though perhaps more vague, than the clear images of the film suggest.

When I left my marriage and moved to a new place, I ripped out the walls between its two rooms. I painted everything white, tore down the ceiling and had a mezzanine built so that each part of the space could communicate. Only the kitchen and bathroom have any defined function. I wanted to live in a tabula rasa. I wanted spareness (a few smart books), humour (a vintage hob kettle I actually use). Above all I wanted the clarity of spaces that had no traditional use, the interior acting — as with La Chinoise and Cléo — as a way to rethink how I wanted to live.

Joanna Walsh is an author whose works include ‘My Life as a Godard Movie’ (Juxta Press, Transit Books) and ‘Hotel’ (Bloomsbury)

Photography: Collection Christophel/Alamy Stock Photo