By Nathan Ma

When I think of my fantasy home, I cycle through the many places where I have lived. For instance, when I was 20, I rented a one-bedroom flat in the heart of Berlin because it was the perfect age to boast about living in the loveliest inner-city neighbourhood, though my flatmate and I took turns sleeping in the bedroom and on the couch. Later, I lived in a spacious flat on a quiet street with a landlady who was permanently absent. She charged us 90s-era rent and in return, we had a toilet flush held together by dental floss. These dwellings were imperfect and noticeably uncomfortable, but I still felt at home in them until my leases ended and I found a new corner of the city to call my own.

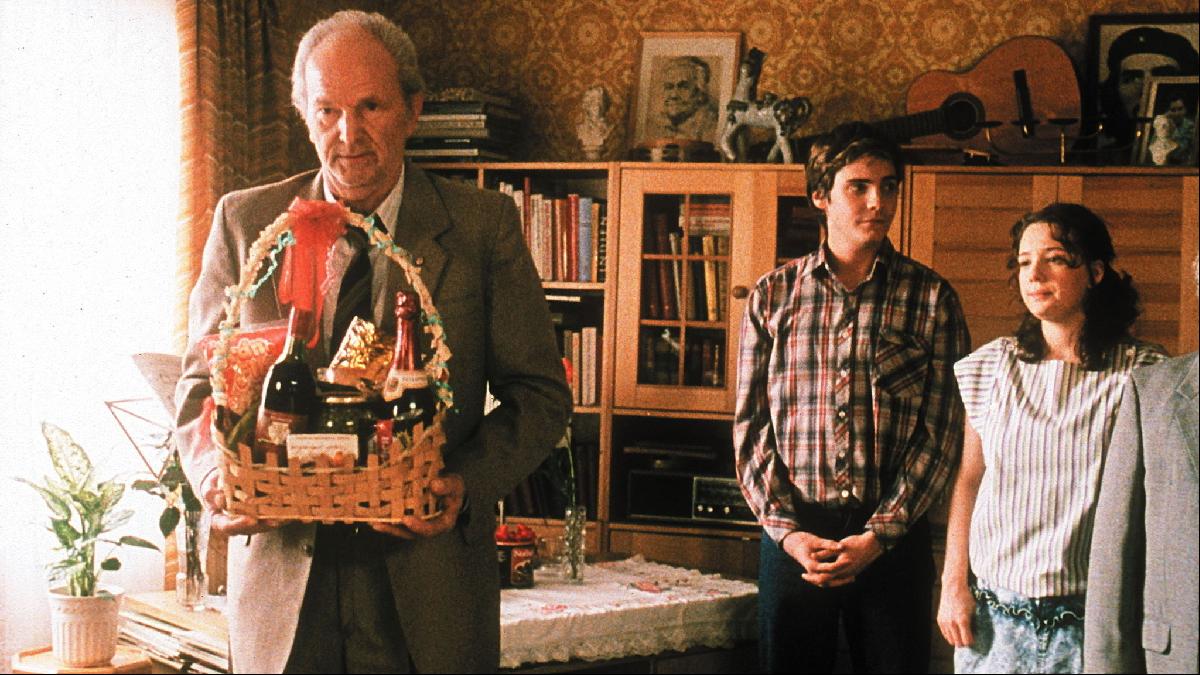

It’s tempting to romanticise these discomforts, which is often the root from which nostalgia grows. In the 2003 film, Good Bye, Lenin!, which is set in East Berlin in 1989, after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, a young man called Alexander (played by Daniel Brühl) must preserve the communist lifestyle for his mother (Katrin Sass) after her doctor warns him that the shock of learning about the fall of the wall could stop her ailing heart. Alexander makes a fantasy home of his own, filling the family flat with their old furniture, East German pickle jars and sachets of discontinued coffee. He shows so much love for the country that raised him that you’d be forgiven for forgetting that his mother’s first heart attack was caused by the sight of Alexander laying on the street, beaten and arrested at a demonstration against the East German government.

The glow of Alexander’s nostalgia for East Germany eclipses the frustrations that led him to the streets that night, and I find his fervent redecorating overwhelmingly romantic. As I’ve grown older, I’ve come to covet his hope and determination. I used to daydream of my fantasy home and I would borrow what I loved about the places I’ve called home, then grimace at what I hated. I rarely lingered on what I could have done at the time to save these real homes from themselves — it was more satisfying to think of the things I might change in the future than it was to go about addressing the things that needed to be changed before my eyes.

I see myself in Alexander more now than when I was younger. Change spurs him on. As Alexander turns back the clock on the apartment he shares with his family, he insists he’s acting with his mother’s best interests in mind but it’s clear his fervent nesting is for his own sake too. Alexander needs a home in which to hide from a world that’s growing increasingly unfamiliar. Western influence moves fast and while he enjoys glimpses of new freedoms, he becomes obsessed with the nation East Germany could have been — a nation where he was cared for, not mocked or abused or abandoned.

He finds this home among the food, drinks and songs he grew up with. He finds this home with his mother and he finds this home with a great deal of hope. Even throughout his eventual grief at the end of the film, Alexander has no grand delusion — the GDR in which his mother does alas die was one that never existed. But it was one he’d made himself and one they both believed in. I cherish Alexander’s fantasy home just as I cherish my own, for they represent something that I now know to be true: home is a feeling worth fighting for.

Photography: United Archives/Alamy; TCD/Prod.DB/Alamy; Photo 12/Alamy