By Thea Hawlin

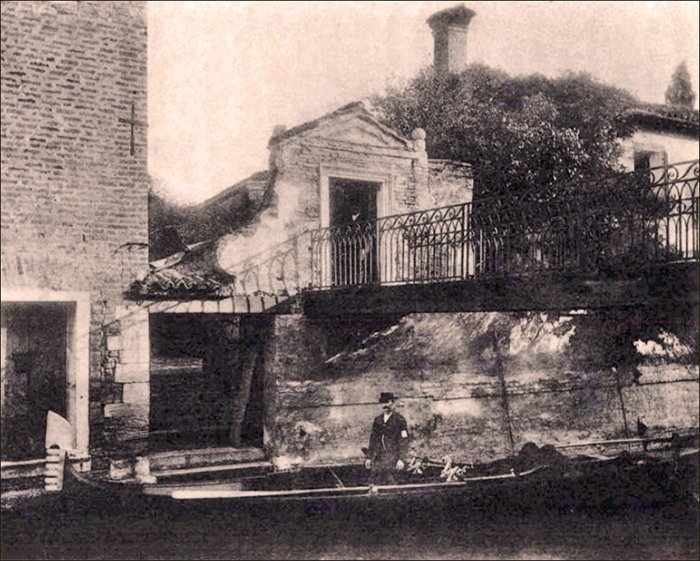

It is difficult to grow a garden in Venice — the salt waters of the lagoon seep into the soil and there’s a reason it’s dubbed “the tomb of flowers”. Despite the challenge, in 1884, an English couple established what was to become Venice’s largest private garden on an old artichoke farm, on the island of Giudecca.

In his book, A Garden In Venice (1903), Frederick Eden (the great uncle of prime minister Anthony Eden) detailed how he and his wife Caroline travelled every day by gondola from their home across the lagoon to care for the garden. They enriched the soil and built a network of willow pergolas covered with roses, underplanted with madonna lilies. Walkways of seashells were lined with cypresses, pine trees bordered manicured lawns where guests lounged in the dappled shade of magnolias. Colour abounded: little yellow buds of pittosporums, blue irises, purple lilacs, fragrant bows of honeysuckle and jasmine. Eden’s spontaneous purchase of a cow from a visiting boat was the start of a small dairy; for a year or two it housed hives of Ligurian bees.

Writers and artists from around the world passed through Eden’s garden. Henry James was a visitor and it seems likely that the “garden in the middle of the sea”, which features in his 1888 novella, The Aspern Papers, is inspired by Eden’s. Jean Cocteau used it as a setting in his poem, Souvenir d'un soir d'automne au jardin Eaden (1909). Gabriele D'Annunzio’s novel, The Flame (1900), recalls its “edges of lavender, its oleanders, its carnations, its rose-bushes crimson and crocus coloured”. Other writers and artists who visited included Marcel Proust, Robert Browning, Isadora Duncan, Eleonora Duse, John Singer Sargent, Claude Monet, Rainer Maria Rilke and Gertrude Stein.

After the Edens, the Greek Princess Aspasia Manos moved in, living there until her death in 1972, when the garden passed into the hands of the Austrian artist and architect Friedensreich Hundertwasser. Although Eden enjoyed mixing flowers and fruits — “delightful… to pick one’s strawberries and cut one’s tea rose from the same bed” — Hundertwasser disagreed with flowerbeds entirely, encouraging thistles and nettles to grow.

Hundertwasser once said that straight lines were “godless and immoral” and his approach to gardening followed a similar vein: "the tangle of undergrowth is a veritable embroidery!”. He preferred to let nature run its course, rarely visiting the garden himself. When he died in 2000, the foundation bearing his name followed his wishes: the door would remain closed to the public and, as the foundation confirms, the garden maintained but left uncultivated.

Adele Re Rebaudengo, the president of the Venice Gardens Foundation, is one of the few people to have visited the garden since it was bought by Hundertwasser. Her organisation recently won a prize from Italy’s National Network of Parks and Gardens for the restoration of the Royal Gardens by St Mark’s Square, and she has made clear to the Hundertwasser foundation her interest in restoring Eden’s garden — and its spirit. “If there’s a tree in trouble, it’s not fated that it should die,” she says, recalling how she was pained by the plants she saw suffering without adequate care. The loss of a solitary tree may work in a large forest, she adds, “but in an urban garden it just doesn’t make sense”.

Eden seems a prophetic name for the garden; like Adam and Eve, we have been cast out. The abandoned watchtowers of an old prison on its northern perimeter tower beside the treetops like guardians. Despite the working doorbell, the door is locked shut and the private bridge to which it leads is a sealed metal cage, flanked by two small security cameras perched upon the brick walls.

Yet a garden “is never made in the sense of finality”, as Eden wrote. “It grows, and with the Labour of love should go on growing.” Re Rebaudengo agrees, “A garden is alive, it isn’t something that should remain still like a painting.” Looking over the high walls, glimpsing cones of cypress trees, and slips of white statues, I spy pale wooden beams latched together to support a newly planted tree. Rumours say a monk on the island holds a set of spare keys; it seems a touch of human care may persist in this hidden paradise after all.

Photography: ‘A Garden in Venice’; Jean-Pierre Dalbéra/Flickr