By Thea Hawlin

When the artist Eli Benveniste first met her future husband, Jørgen Haugen Sørensen, she wasn't sure who she fell in love with first: the artist or his house. Benveniste had been visiting the Tuscan town of Pietrasanta in the 1980s with a friend when she ran into Sørensen, a Danish sculptor who — like Michelangelo and Henry Moore — had been drawn to the area for its marble quarries, stone workshops and bronze foundries.

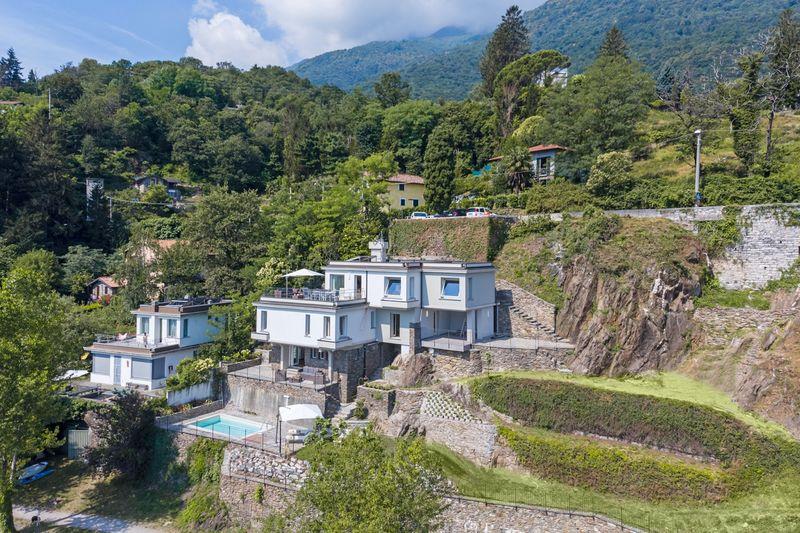

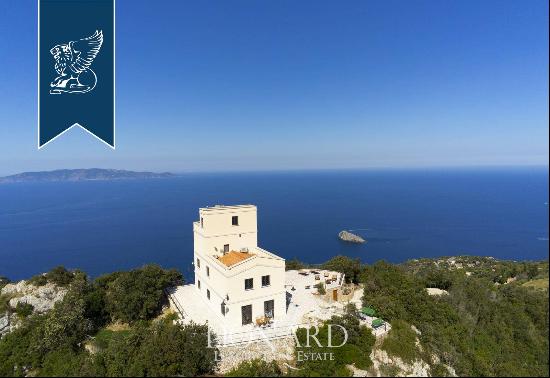

Sørensen invited them back to his home, a 15th-century villa situated in the Versilia hills between the Apuan Alps and the Mediterranean Sea. The scenery certainly made an impact: from its elevated position, a 10-minute drive from Pietrasanta, the house has a panoramic view over the Tuscan countryside to the Ligurian Sea. “It’s special,” says Benveniste. “It’s not just a line of water — you can see the three islands of Palmaria, Tino and Tinetto, just off the coast of Porto Venere.” The four-bedroom property is on the market for €2.4mn.

Sørensen had bought Villa Simi in 1983 with his first wife, Jette Mühlendorph Christensen, an art historian, when it lacked a roof and a fig tree was growing in the kitchen. “It was in a very bad state,” says Benveniste. “They had just sold a house which had been completely restored and he felt he had ruined it, so he decided he would change the villa as little as possible. It takes a lot of courage and a good eye to let things be as they are.”

Thanks to the renovation and Sørensen’s subtle interventions — including metal supports to reinforce the stone floor — the spirit of the house survives: the walls in several rooms appear untouched, coloured with the soft traces of their original frescoed designs.

The villa was built in the 15th century and then bought by the Simi family, who made their fortune trading marble. In 1778, it was extended and renovated by the aristocratic Pisani family, giving it an elegant “U” shape.

In addition to the bedrooms and two bathrooms, the property includes a library and a chapel — which Sørensen used as a studio — dedicated to St Anthony of Padua. The chapel was also transformed for entertaining. “Once we were sitting with 40 people [in there], with the food up by the altar,” says Benveniste. “I had to organise a kind of one-way system, and then we pushed the tables to the side and danced. We’ve done a lot of dancing in that chapel!”

The villa is surrounded by lush gardens and paved terraces — at the front of the house, with the view of the sea, and at the back — that act as extensions of the interior. “It’s a fun house … it gives you a lot of freedom,” says Benveniste, recounting how its layout allowed them to have breakfast basking in the morning sun, to follow the shade on hot summer days, and drink cocktails admiring the sunset. For years she worked in one of the annexes in the lower garden near a circular stone pond that has lily pads and goldfish, creating her sculptures in clay, several of which currently sit upon the garden walls. When Sørensen also started to work in the medium, the couple invested in an on-site kiln and frequently swapped studio spaces over the years.

Sørensen died in 2021 and Benveniste is now ready to move, though she won’t be going far. Sculptures by her and Sørensen can be found throughout the house, most notably lining the grand entrance hall, some of which the new owners will be given the opportunity to buy. She already intends to leave several sculptures that have become intertwined with the identity of the house, including a ceramic by the pond and two reliefs by Sørensen on the exterior walls of the villa, accompanying older historic plaques such as the property’s original coat of arms. “[The house] will still hold the traces of the sculptors who lived here,” says Benveniste, “I will make sure of that.”

Photography: Italy Sotheby's International Realty