By Chris Hayes

It’s clear that deindustrialisation has not spelt the end for factories. While many have been torn down to make way for new construction, those that have survived are often now seen as highly desirable design destinations. This began with the artists and bohemians in search of cheap rents and spacious floor plans in 1960s New York.

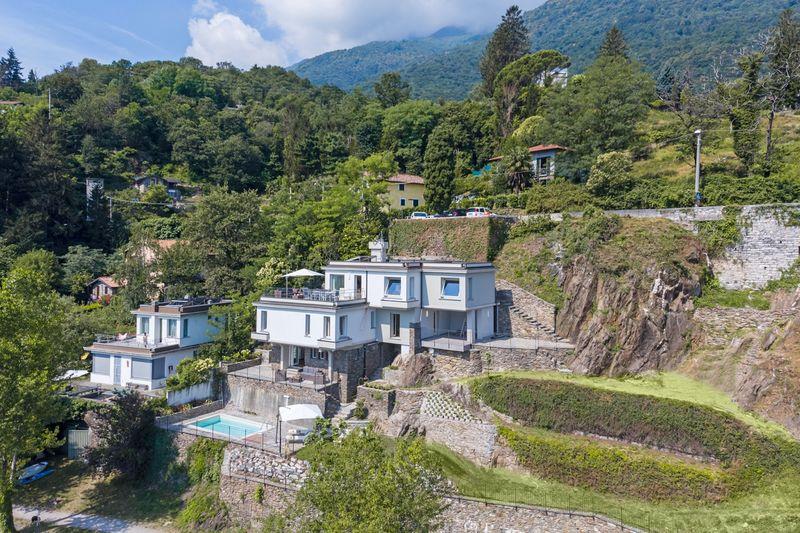

Now Florence has a new vision for its industrial past. The Manifattura Tabacchi is a former tobacco factory in the north-west of the city that has undergone a sweeping reinvention. Built in the 1930s by architect Pier Luigi Nervi, it officially opened in 1940 employing 1,400 workers making cigarettes and cigars. Designed as an innovative industrial complex, form followed function, with the offices and a theatre at the front, warehouse buildings at the back and the main factory in the centre.

The vast 110,000 sq metre site closed in 2001, but has now reopened as a contemporary community hub for Florence. There are restaurants, Pilates studios, barbers, tattoo and piercing parlours, exhibition spaces, artist’s studios, ateliers and a new nursery. One thousand trees have been planted, while a hidden botanical garden is being created on the roof promoting the biodiversity of the Tuscan landscape. There are residential offerings, too.

The first phase to launch were the lofts, all of which have been sold. The second phase includes a series of apartments designed by Patricia Urquiola. One three-bedroom flat, with large, open living spaces leading directly out on to the building’s panoramic terraces, is currently on the market for €1.8mn.

As with many industrial developments, the building’s functional origins are reflected through style. Economic pragmatism often shaped the design vocabulary of factories. Straight lines and minimal forms were practical, often the most cost-effective option, yet they also have a confident aesthetic that has charmed and inspired some of the most influential architects of the 20th century — think of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation and Richard Rogers’ inside-out building.

A desire to preserve their form is nothing new. Architecture critic Jane Jacobs was a prominent advocate for preservation over demolition. Her 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities pushed back against decades of public planning orthodoxy which favoured tearing buildings down to construct large highways and skyscrapers, a position she felt so strongly about it led to her arrest in 1968 for inciting a crowd at a public hearing.

Deindustrialisation created a supply, yet it’s perhaps the mainstream newspapers and style magazines that laid the path for reinvention. The New York Times wrote a series of articles from the 1960s to the 1980s, at first noting the novelty of artists living in lofts, such as Gilbert Millstein’s 1962 “Portrait of the Loft Generation”. As it became a more established and desirable option their reporting turned to the design challenges posed by such bare walls, high ceilings and generous proportions: “too overpowering,” according to one article in July 1980, noted by sociologist Sharon Zukin in her book Loft Living.

Even today, the choice of materials used in the construction of factories contrasts with the growing use of cheaper faux alternatives, particularly for brick facades, in modern residential construction, ironically appearing more luxurious by contrast. Weighty by look and feel, industrial architecture has often evoked favourable comparisons with the past. On a trip to the US in 1913, modernist architect Walter Gropius famously declared that its factories “almost bear comparison with the buildings of Ancient Egypt”. In Florence, the new Manifattura is built on strong foundations.

Photography: SAVILLS