By Edwin Heathcote

Some cities conjure up images of one-off houses, individual architectural statements that stick out in the streetscape. Think of Tokyo, Los Angeles, Brussels and Seoul. But London is not one of those cities — with its history of understated terraces, a future of generic towers and a demanding and often unbending planning system, the capital of the UK rarely lends itself to individual statements of architectural intent. And while the wealthy might manage to build something of interest, such houses are often obscured behind high walls and hedges.

So when a striking new house does come along, it makes an all the more surprising statement, a moment of delight in its departure from the norm. The most recent is an unusual and delightful home that plays with postmodernism, constructivism and the London vernacular of inner city council estates. It stops you in your tracks, in the best possible way.

Designed by Sam Jacob and wrapped around a long-defunct pub in Hoxton, the house sits on an awkward site — a leftover plot, characteristic of the often uncertain junctions between private and public space. The building takes its character directly from the ambiguity of its location. “One day, the planners drew a shape on a map,” Jacob tells me as he cheerily bounds around the site. “[It was] completely arbitrary. But then the map becomes the territory.”

The house’s distinctive bullnose gave Jacob the form of a cylinder with a spiral stair. To anyone with a little knowledge of radical 20th-century architecture, this structure will invoke one building more than any other: Konstantin Melnikov’s Moscow house, begun almost a century ago, in 1927. A strange, enigmatic dwelling, this white cylinder with its hexagonal windows has become a pale ghost, haunting all subsequent cylinders. But if Melnikov’s house was a standout piece of eccentricity, a chapel of modernism in the streets of Arbat, Jacob’s house draws its materials, its language and its form from the back streets of Hoxton. It doesn’t exactly blend in but it does draw on familiar elements.

The most obvious is its external stair, which wraps around the curve and deposits the visitor on the first-floor landing. The house is situated where Victorian Hoxton Street meets the long stretch of postwar council estates sprawling towards central London. It manages to imbibe both architectures. The external entry and landing reflect the gangways and access decks of the council blocks (the once-feted “streets in the sky”).

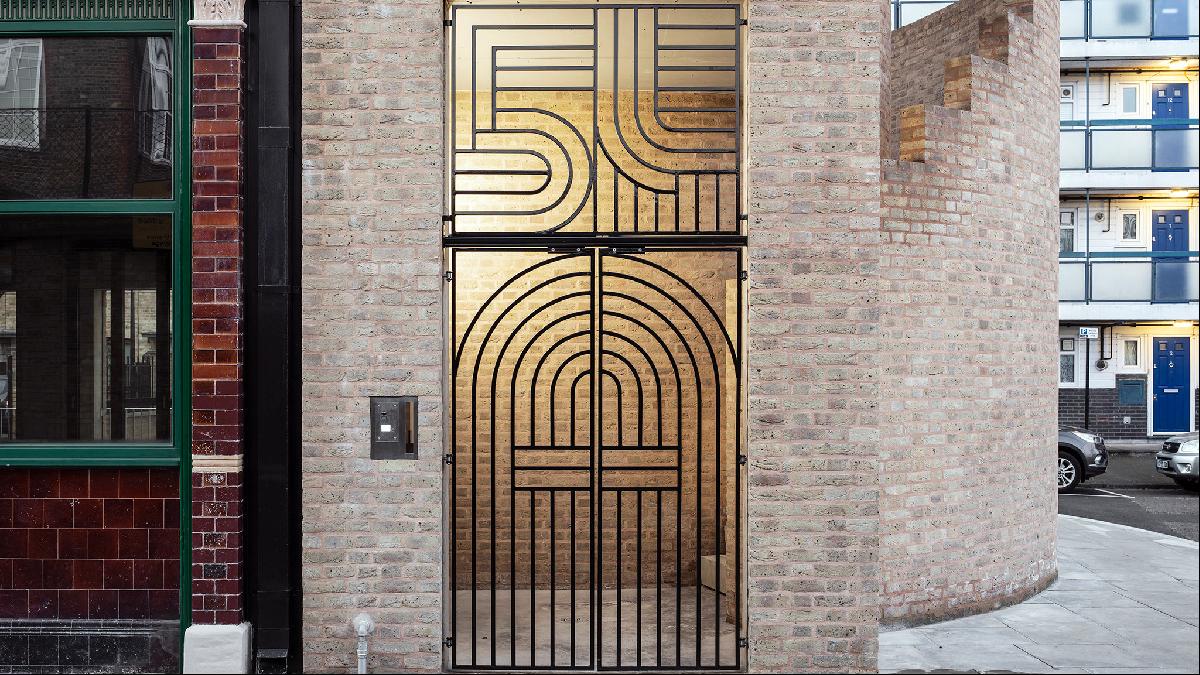

A steel gate, with a 1970s-looking, oversized number 54 inscribed in the bending of its bars creates a vivid nod to New York’s Studio 54 nightclub. The stepped wall wrapping round the external staircase lashes on a little postmodernism (pomo) and whisks the visitor into a galleried, double-height living room — a theatrical and totally enjoyable space. It looks like it might be a converted water tower or grain silo, with diamond-shaped openings punched into its curving walls. Other rooms are a little more conventional, though the kitchen and bathrooms each revel in a splash of 1970s Conran-era colour.

Above the main living space is a roof terrace. The views give all the cues for the architecture, the mix of Victorian and modernism: the backs of the houses with rear additions and ad-hoc extensions; the access balconies of the council flats. A wood-clad cylindrical shed tops it off, another echo of New York and its roof-top water towers, as well as a homage to this complex London roofscape of lift machine rooms and escape stairs.

At street level, bits of an old pub survive and these have been given over to the former occupants of the site, the Ivy Street Family Centre, a charity and crèche, which assists new mothers in the neighbourhood. The institution was keen to stay on the site where it was a familiar and trusted refuge. If most new London houses revel in a kind of exclusivity and expense, this one is rooted right in the estates in which it is set.

Witty, warm, charismatic and a little enigmatic, Jacob’s house is a welcome revival of a kind of pomo pleasure in architecture that has been largely lost. The effect is reminiscent of the Blue House in Bethnal Green, designed by Sean Griffiths, Jacob's former partner at FAT — or Fashion Architecture Taste — architects. Griffiths' splash of surreal colour and childlike wonder, with its painted clouds and toytown facade, is now 20 years old. Jacob’s Hoxton home eloquently makes the same point — that a house can be both a private place and a public pleasure.

Photography: Johan Dehlin