By Imogen Lepere

The gentle chug of passing boats and the squawk of seagulls is part of what makes life in London’s W4 so desirable, but few houses offer a better window on to river life than Strand End. The detached five-bedroom villa and adjacent boat shed were built in 1869 for prominent shipwright Francis G Maynard. Though the boatyard has long since closed, the property, which is on the market for £4.25mn, still benefits from its proximity to the River Thames, with the courtyard garden running down to the water’s edge.

“When they were younger, my children spent many happy hours fishing, while the private slipway made it easy to launch our dory [small boat],” says Professor Peter Hill, who bought the property with his late wife, Christine, in 1985.

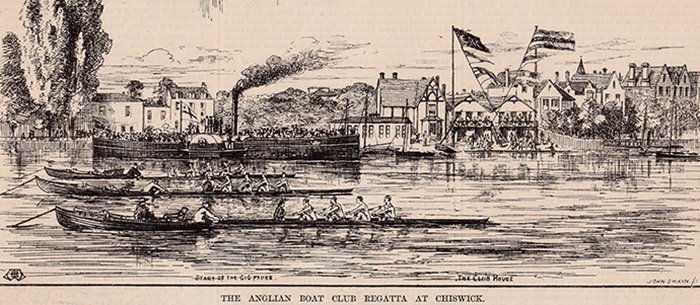

Maynard’s was originally part of a much larger complex, with two two-storey boat sheds to the east of the main house. The place was a centre for society boating: as well as building vessels for the Rothschilds, the Earl of Cairns and Italian aristocracy, Maynard rented boats to the gentry and organised regattas from Putney Bridge to the yard.

It was also a place of invention. While living here, Maynard designed many non-powered boats and developed the innovation he is best known for: a canoe made of laminated paper — a forerunner of fibreglass, which is still used today for racing yachts. His business card from the early 1880s describes his boatyard as the “Builder of The Willesden Patent Waterproof Paper Boats”. Many rowers also used the yard, assembling and collecting boats for events including the annual University Boat Race.

Hill carefully restored the house over a period of 20 years and converted the surviving boat shed to a studio for Christine, who was a leading antenatal expert. She used the light-filled space to offer classes to pregnant women, including the Princess of Wales as she prepared for the birth of Prince George in 2013.

“The house has been well-used and well-loved by so many people,” says Hill. “Although the boat shed does have a private entrance we decided not to build a separating wall. I love the fact I can be in my study there without being sealed off from my grandchildren in the kitchen.”

When the Hills bought the property it was in a state of disrepair — “riddled with wildlife, including ducks” — and they did most of the work themselves with the exception of flood defences that were installed by the Greater London Council.

The main house is characterised by original details including portholes in the front door, a Victorian staircase, wood-burning fire and bay windows in the main reception room. The master bedroom on the second floor has a vaulted ceiling and views across the river to Oliver’s Island, beyond Kew Railway Bridge.

The house might have been an integral part of Chiswick’s thriving boat building industry during the Victorian period, but today its selling point is its tranquillity. “Of course the river is always there, but the view changes constantly. When the tide is in, it feels like living on a boat. The sun sets directly across the river and it’s wonderful to watch the light shining through a row of horse chestnut trees in front of the National Archives.”

Over the years, the Hills built up a logbook of the flora and fauna that can be seen from the house and its immediate surroundings: kingfishers, herons, bream that jump out of the water at the turn of the tide. “It’s special for children to be able to learn the rhythms of the river while also being able to reach central London in 20 minutes.”

“Of course, I will miss it but it’s really too big for me,” says Hill. “Maynard’s grandson, Frances, described it as ‘my family’s house, secure, well-ordered and happy beside the water’ and it really does feel like that when you spend time here.”

Photography: Savills; Courtesy of Seran1926