By Miriam Balanescu

Although there are several hundred mews houses in London alone, it can be rare to stumble across them serendipitously. By nature, a mews is designed to be kept out of sight. One of the earliest uses of the phrase “in meuwe”, found in the 14th-century romance poem William of Palerne, referred to “caitliffs”, or cowards, stowing away to avoid battle. Later in the Middle Ages, the word often alluded to a secret hiding place. With many mews now protected by conservation regulations, they remain quiet, cobbled refuges away from the nearby hustle and bustle of cities.

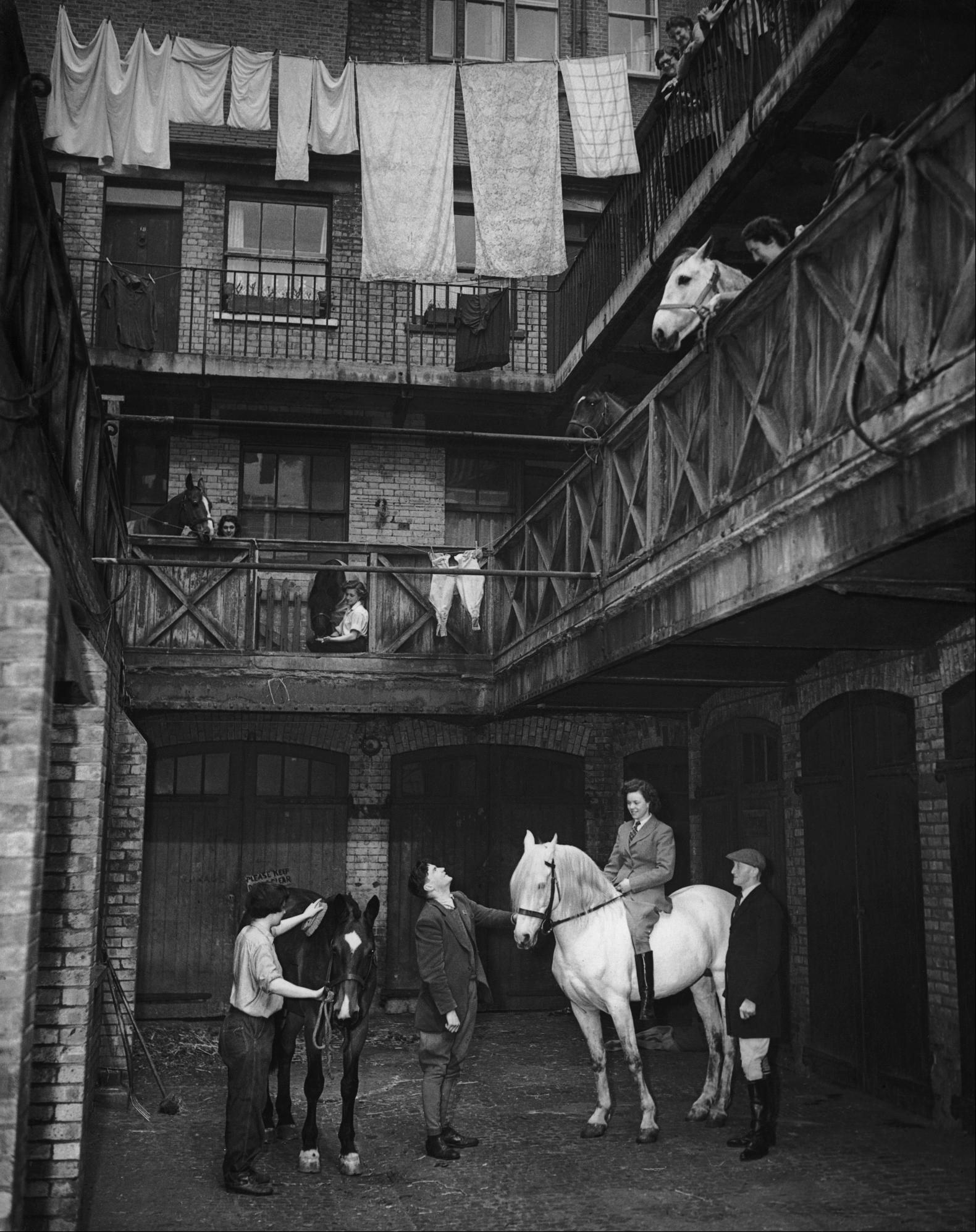

Before they became desirable abodes, mews had long been home not to humans, but animals. Originally, they were bird coops, for fattening or breeding poultry, or sheltering hunting birds while they shed their feathers — mews comes from the French word for moulting, muer. In the aftermath of a 1534 fire that razed Henry VIII’s stables to the ground, however, the fowl at the Royal Mews were supplanted by the King’s displaced mounts. The name endured, and thus the buildings became associated with horses.

Despite their modest proportions, these neat rows of houses sprang up in the wealthiest areas of cities — constructed for those who could afford separate quarters for their steeds. As 18th-century London sprawled further into the undeveloped pastures that became neighbourhoods such as Belgravia, Chelsea, Kensington and Mayfair, its Georgian town planners allowed for grand town houses backed by cloistered streets of stables and coach houses, with accommodation for grooms and coachmen above.

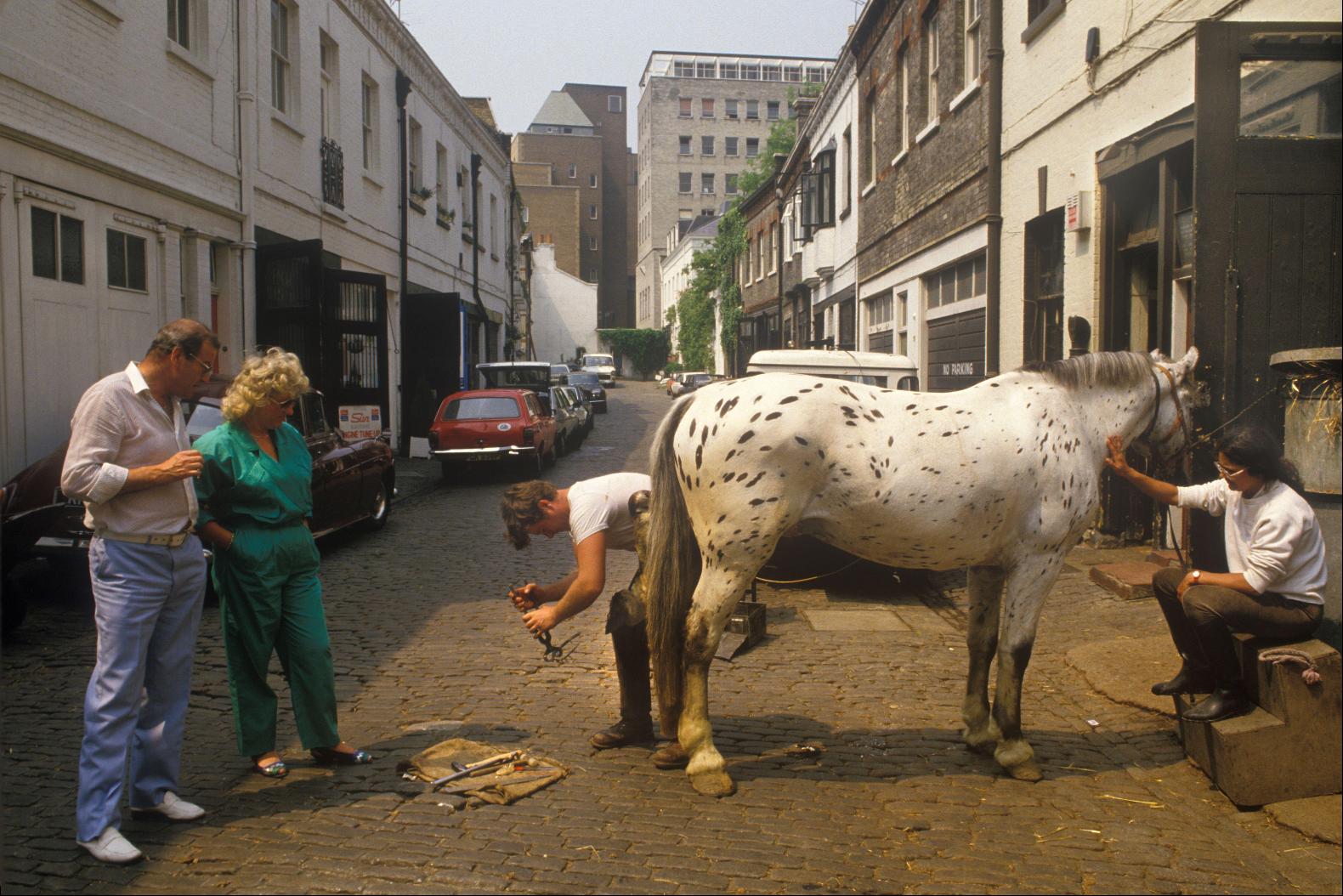

The heyday for these equine lodgings was the 19th century. In 1825, Neoclassical architect John Nash — who also transformed what was then called Buckingham House into the present-day palace at the behest of George IV — constructed the current Royal Mews with a budget of more than £65,000 (£5mn in today’s money). Although most densely found in London, mews were also built during this period in other English, European and American cities. But within 100 years, the motorcar had begun to oust the horse and carriage as the most common means of transportation.

The first and second world wars, and the accompanying blows to the economy, reduced the numbers who could afford town houses in their original form. Pressures spiked as populations rose and, increasingly, led to property conversions, their progress stalled only by legislation such as the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947.

Having fallen out of fashion during the previous 50 years, the 1960s ushered in a resurgence of interest in mews properties. The two-floor layouts made them ripe for renovation into family homes or division into flats, and their secluded nature enticed celebrities and artists: the Sex Pistols’ Sid Vicious rented a flat at Pindock Mews, Maida Vale; Michael Caine at Albion Close, Hyde Park; and Formula One driver James Hunt at Normand Mews, Barons Court. On moving into an unassuming studio in Reece Mews, South Kensington, Francis Bacon is quoted as saying: “The moment I saw this place I knew that I could work here” — he painted at the property until his death in 1992.

Mews have also been sites of literary inspiration: in Agatha Christie’s Murder in the Mews (1937) and Margery Sharp’s Britannia Mews (1946), these little nooks of lanes and alleys are sites of intrigue and contrast. The writer Joy Packer even chose to centre a twisty spy plot around these quaint homes in her 1964 novel The Man in the Mews.

With their preserved features and contemporary revamps, the mews house is where history and modernity collide. We see this perhaps mostly clearly at Bathurst Mews, Hyde Park where, during renovations, residents ensured two properties were kept as functioning stables.

Photography: Kristina Blokhin/Alamy; Don Price/Getty Images; Homer Sykes