By Edwin Heathcote

In 1947, Hollywood studio session musicians Ray Siegel, Jules Salkin, Gene Komer and Leonard Krupnick grouped together to buy a plot in Brentwood, Los Angeles. Disillusioned by the boxy apartment blocks that had recently become available in the city, the friends determined to build a green community. They formed the Mutual Housing Association and conceived their development as a place of community, amenity and shared lifestyle, rather than investment or speculation. Critically, they were determined to make it a racially integrated development, free of prejudice and discrimination, to the great offence of some local residents.

Architects, A (Archibald) Quincy Jones and Whitney R Smith were hired alongside progressive landscape architect Garrett Eckbo to masterplan the project and draw up design patterns for houses based on prospective residents’ needs and desires. Jones was a prolific architect and is thought to have had a hand in the design of as many as 5,000 buildings, from homes for movie stars (Gary Cooper’s wonderful Holmby Hills house) to affordable tract housing and suburb plans. His integration of landscape, greenery and architecture drew on his experience designing housing for workers in California’s burgeoning wartime arms industries and proved hugely influential in the postwar suburban boom.

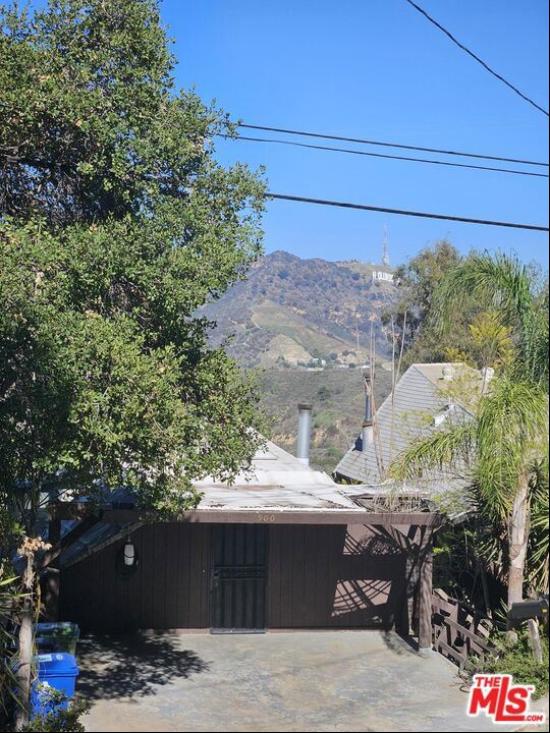

Jones's quiet modernism rarely attracted the kind of adulation enjoyed by some of his peers, such as Philip Johnson, Eero Saarinen or his architecture school classmate Minoru Yamasaki, the designer of the Twin Towers in New York, but it has lasted well. One of the earliest of the Brentwood houses, the three-bedroom Hart Residence, built in 1950, is now on the market for $3.989mn, following a long process of updating and refreshing by developers HabHouse, a firm specialising in the refurbishment of historic houses.

This is a simple, modest home, carefully designed and carefully (albeit heavily) restored using the architects’ original palette of material and colour. At one end is a large living/dining/kitchen space with glazed walls. The plan pivots around a freestanding chunky concrete block and brick fireplace (with a curious tubular chimney). This defines, on the other side, a more private “den” and leads to the three bedrooms. Set into a steep slope, the changes in level inside allow a little architectural invention where, for instance, the bedrooms are not overlooked by other houses and have views up to the landscape above through high level windows.

Jones’ designs are often characterised by walls that don’t fully reach the shallow mono-pitch roof, allowing light to flow through the plan. Similarly typical is the bare blockwork walls and built-in plywood storage and cupboard spaces, heavily rebuilt here but absolutely in the spirit of the original. These were cheap, mass-produced materials designed for affordable houses, though there is the occasional highlight of more luxurious timber, such as built-in wardrobes in the bedroom and on the porch. The car port — an extension of the roof supported on simple steel columns — is itself a perfect period piece; mobility and Californian freedom expressed rather than concealed in a garage.

The biggest thing that has changed is, arguably, the price. What were once determinedly affordable houses for Bohemians on a budget are now in the millions, as this progressive neighbourhood has become progressively more desirable. But what a piece of west coast modernist history.

Photography: Cameron Carothers / NRT Sotheby’s International Realty