By Edwin Heathcote

With his surfing obsession, leading-man looks and Hollywood lovers, Harry Gesner was nothing like the traditional image of an architect. Perhaps this has something to do with the fact that the self-taught designer was not, technically, an architect.

Despite this (or perhaps as a result of it), Gesner, who died last year, at the age of 97, was one of the most interesting, radical and individual architectural designers of mid-century California. While his contemporaries were designing glass boxes and minimal villas, Gesner was knocking out futuristic forms, wacky shapes and sci-fi fantasias.

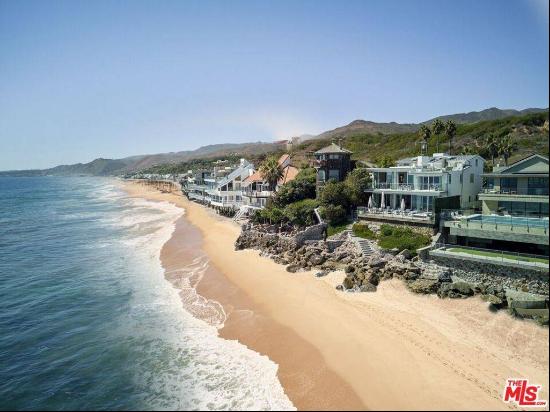

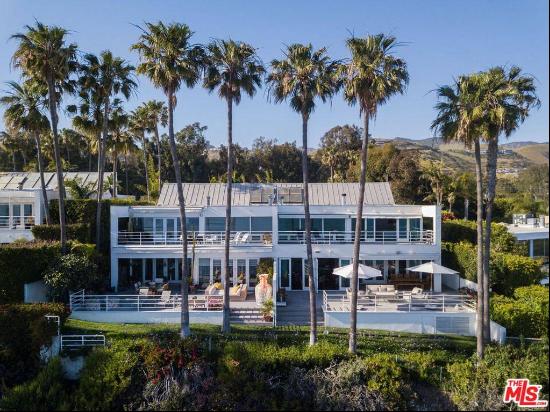

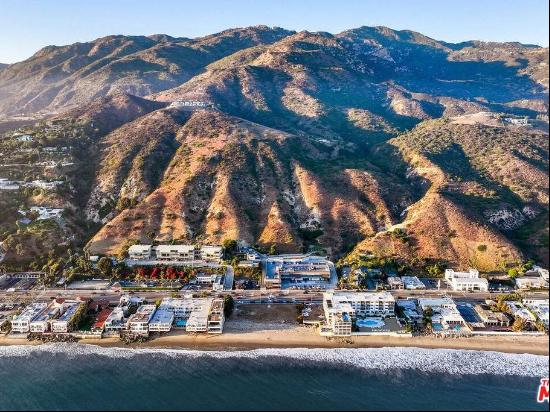

The Wave House, which is currently on the market for $42.5mn, is one of his best. According to Gesner, he designed it while looking back at its site on Malibu beach from his surfboard in the Pacific, sketching out its profile in wax pencil on his board. Its organic, cresting wave roof, clad in fish-scale-like patinated copper tiles seems to prefigure everything from the Sydney Opera House to Frank Gehry’s wilder works.

Born in 1925, Gesner’s early life reads like an unlikely movie. He could fly a plane at the age of 14 and, having joined the military at 17, became an army ski instructor before he was launched into action in the D-Day landings of 1944. (He credited his experience as a surfer with his survival at Omaha Beach, where the landing craft had to stop short of the beach and soldiers made their way to shore themselves). After the war he was talent-spotted by Frank Lloyd Wright but declined to study with him, instead going on an expedition to Ecuador and spending time in Mexico (where he became friends with actor Errol Flynn). Eventually, he returned to California to work with his uncle’s construction firm and learnt the trade.

His first notable project was the striking Eagle’s Watch house he designed in Malibu in 1957 (now available to rent on Airbnb). The difficult, sloping site could only be reached by a funicular and its extravagant form was apparently inspired by the wings of an eagle he observed flying above the intended site. It garnered extensive publicity with its swooping rooflines, appearing in magazines around the world and confirming California’s kooky architectural reputation.

The Wave House was designed around the same time but took a little longer to finish. Elevated above the beach on concrete stilts, the house thrusts itself out towards the ocean like the prow of a ship. If the roof looks familiar it might be because there is a passing resemblance to Jørn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House, which was designed at the same time. The two architects were familiar and admired one another’s work, though both denied that one had influence on the other. It is also reminiscent of Eero Saarinen’s expressionistic concrete roof for the TWA terminal at New York’s JFK airport (1959-62). There was clearly something in the air.

Gesner’s roof in Malibu was in timber rather than concrete and is formed from a series of complex constructions that conspire to appear deceptively simple. The house centres on a broad, circular conversation pit with a fireplace and chimney breast sitting at its apex. It’s perhaps an odd foreground for a Malibu ocean view but it was very much of its era and maybe a throwback to Gesner’s skiing days.

A more conventional accommodation block sits behind the extravagant structure — not the most elegant solution but it helps maintain the purity and sculptural effect of the beachfront element. The large decks are arranged in a cloverleaf plan, with wonderful views over the ocean.

Unlike in the original designs, there are also handrails, which were added by Gesner at the request of Rod Stewart, who owned the house for a time in the 1970s and was concerned about party guests falling on to the beach.

Gesner built a base of playboy clients who were attracted to his unconventional but undeniably sexy design. He was a friend of Marlon Brando and tried to design a house for the actor but found his attention span too short.

Though famous he remained an outsider in architecture. He was, however, a real pioneer and an early advocate of environmentalism. He was also an engineer who converted his petrol-powered 1959 Mercedes to electric in the 1990s and patented a system for transforming solid waste into fuel.

This is a wonderful house and a rare chance to pick up an architectural gem. And for those who can’t quite stump up the cash, there’s always Gesner’s home, the Sandcastle (1974), right next door — currently available for a much more affordable $22.5mn.

Photography: Simon Berlyn