By Edwin Heathcote

The contemporary house is not necessarily a place for separation or privacy. For decades the trend has been towards open plan and the knocking through of once discrete spaces. Whether we live in a modern house with its self-consciously flowing spaces, or an upcycled Victorian home with its downstairs converted into a simulacrum of an urban loft and its kitchen sprawling into the patio, the last few months of working from home might have led us to question this spatial orthodoxy.

Perhaps it might, after all, have been better to have a few smaller rooms with doors that can be closed to keep out the noise and distractions of everyday life.

If there is any garden left (after that kitchen extension), we might have considered constructing a separate room in the garden, away from the exigencies of everyday existence. It is what writers, who have never needed to go to an office yet still need to be able to work, have been doing for a very long time.

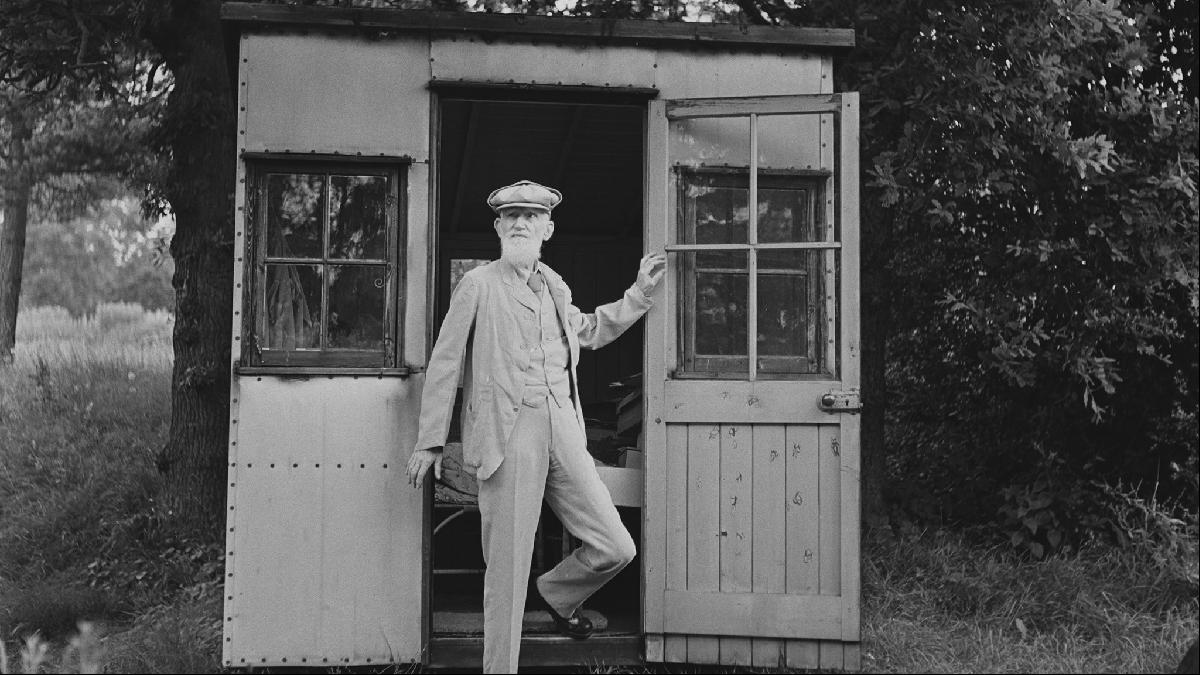

George Bernard Shaw had a seemingly simple but very natty writing shed in his garden in St Albans. Set on a turntable, it was able to rotate to allow him to follow the path of the sun throughout the day. Virginia Woolf, too, wrote in a shed at Monk’s House in East Sussex. Her simple, well-lit, modest room of her own might be a model for shedworking.

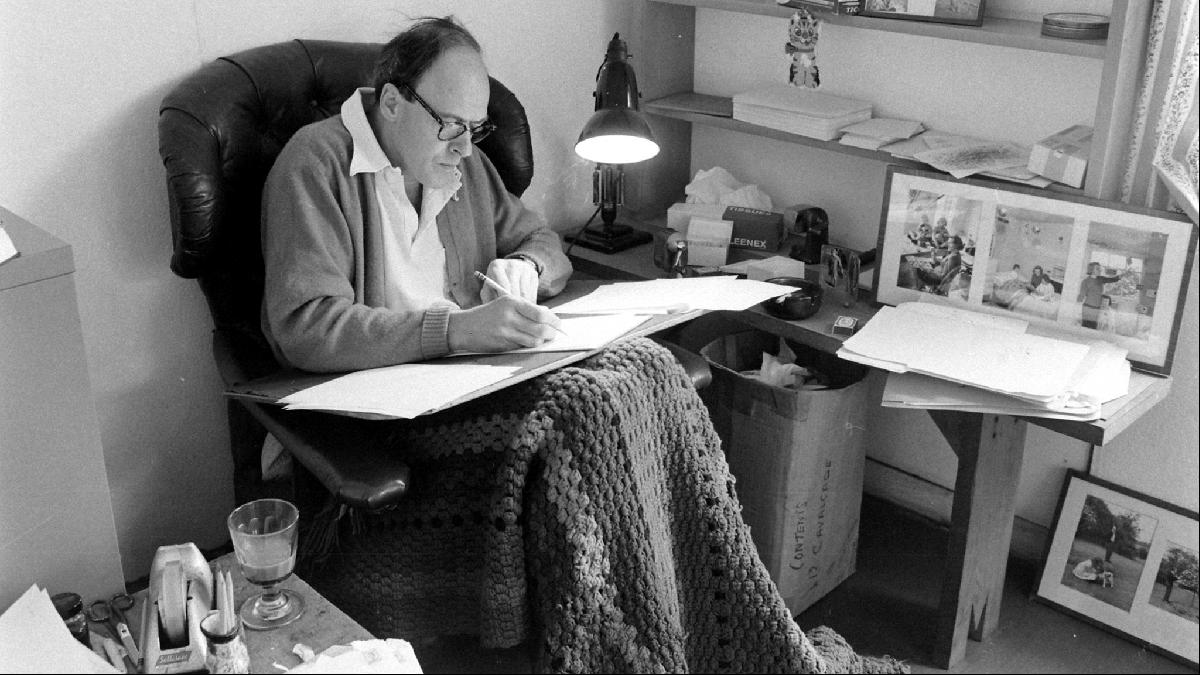

Roald Dahl famously worked from a fabulously shabby armchair and improvised writing board in a writing hut at his home in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire, which was in turn inspired by Dylan Thomas’s adapted bike shed. Thomas’s green-painted timber hut was close to the Boathouse in Laugharne, Wales, where he spent the last four years of his life and wrote his best-known works.

The garden room or shed has remained popular ever since, with writers Neil Gaiman and Philip Pullman working in a garden gazebo and a basic garden shed, respectively.

We might have abandoned the commute for the moment, perhaps even for ever, but the idea is that a shed or a garden studio gives us a semblance of separation between home and work — more crucial perhaps than ever now that our connected lives have digitally entwined the two states. That little spatial separation might be just enough.

The web is awash with home offices and garden studios, from basic to bespoke, but there is, as ever, a next level solution: the architect-designed studio. The modern version of the writer’s hut has popped up in Melbourne, Australia, where architect Matt Gibson designed the small space in a suburban garden. Covered in ivy, the cabin fades into the foliage and green of the garden.

Inside, all appears light, bright and airy. The large desk-height window gives the client a view to the garden but the viewer a glimpse into the studio with its plywood walls, shelves and built-in furniture. Faceted surfaces and unexpected angles give a little lift above the more characteristic shed aesthetic.

A little less polished and built from cheaper materials, Parsonson Architects’ garden studio for a couple in Wellington, New Zealand, is a smart solution taking the opposite approach — getting the kids out of the house into a cool, oriented strand board-clad interior and leaving the home a little quieter. The mix of boarding, timber studs and translucent corrugated polycarbonate gives a nod to Antipodean vernacular as well as Frank Gehry thanks to the neatly constructed covered terrace at its front.

Studio Ben Allen designed one of the most striking recent garden studios for the London house belonging to Allen’s brother. The octagonal pavilion (main image) is clad in variegated green timber elements intended to camouflage the structure into its garden setting. This is, I think, a gag.

It was allegedly inspired by the garden follies of 18th-century houses and, in particular, the marvellously exotic 1761 Dunmore Pineapple pavilion in Scotland, attributed to William Chambers, who also designed Somerset House and the pagoda in Kew Gardens. An artichoke has replaced the pineapple as the exotic formal inspiration but the element of playfulness has survived utterly intact. A central skylight illuminates the interior and the furniture is built-in, including a desk at a window.

Most ingenious though is the flat-pack construction. With elements cut and drilled off site, the whole thing almost snaps together and is completely demountable.

You may even already have some kind of structure in the garden to reuse. The reimagining by Sue Architekten (now Franz&Sue) of a 1930s garden shed in the Vienna woods in 2016 shows what can be done with a delightful difference between interior and exterior. The outside, with its black stained boards, is utilitarian and austere; the interior light, bright and airy, enveloping the space in light timber.

At the other end of the spectrum is Eric J Smith’s design for a writing studio for banker-turned-poet John Barr. The former president of the Poetry Foundation commissioned the structure for his wooded garden in Greenwich, Connecticut, and had it cantilevered over a rocky outcrop. Designed to contain his poetry library and as a space to write, it is built in a slightly Frank Lloyd-Wright-ish combination of glass, timber and rubble stone.

Most of us are unable to escape to an outhouse in our own woods but, as these occasionally modest — and occasionally extravagant — structures show, even a scrubby patch of garden can become a space to work. On the other hand, considering the ill-effects of lockdown, you might wonder whether that little scrap of open space might be the last bit of fresh air left.

Sometimes it might be better to take out a chair and table, and leave those trees in place.

Search for homes with garden rooms on FT Property Listings.

Photography: Ben Tynegate; George Konig and Chris Ware; Keystone Features; Hulton Archive; Getty Images; Leonard Mccombe; The Life Picture Collection; Shannon McGrath; Durston Saylor; Franz&Sue; Andreas Buchberger