By Miriam Balanescu

What is it about landmarks that inspires reverence? From the boom of Big Ben’s clock tower to the solid columns of the British Museum, these significant spaces are the markers that help us form our sense of place.

Before Google Maps, landmarks were beacons that helped wayfarers and sailors to navigate their path. Yet the original sense of the word was more literal. In Old English the concept of a landmearc was domiciliary, something marking a boundary or the limit of an estate. It was only from around the 1560s that the word stopped being used as a reference to physical thresholds.

Striking monuments are still imbued with a sense of liminality, they stand on the edge of things, commanding our gaze and compelling us to stop and take stock. On the skyline, the sharp tip of the Shard meets the curved dome of St Paul’s. And such buildings often come to define an area — St Paul’s is a neighbourhood and a Tube station as well as a cathedral.

Homes within striking distance of landmarks are unique and highly desirable. For Reem Bassatne, owner of an apartment in Albert Mansions overlooking the Royal Albert Hall (main picture, top), the greatest boon is having a room with a view. “If there’s a concert, or the royal family is showing up, all of us are at the window, looking down and seeing the crowds,” she says. “People travel to the Albert Hall just to see what we see when we look out of our windows.”

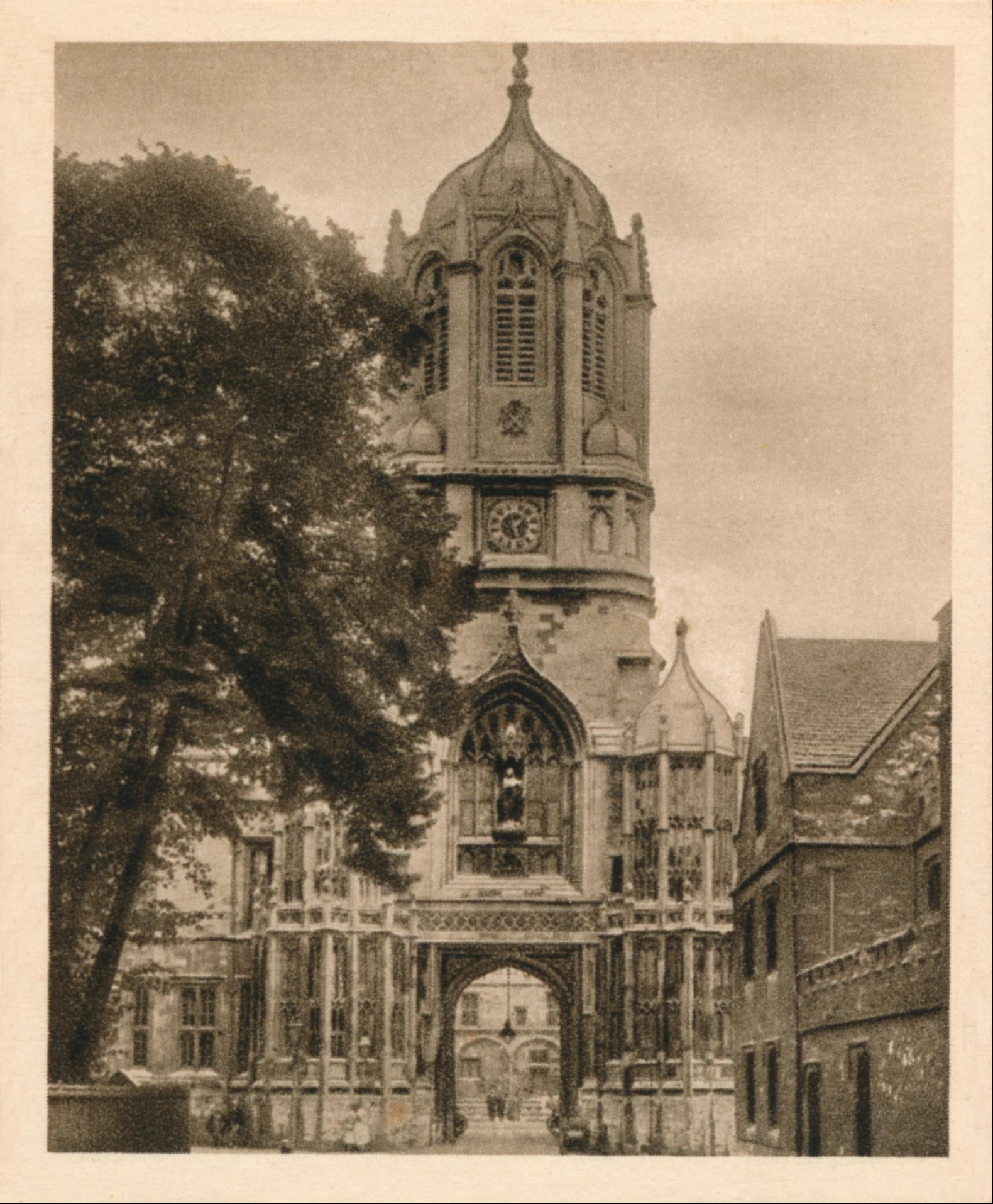

Landmarks can also serve as creative muses. Poet John Keats penned “Keen, fitful gusts” after meeting fellow writer Leigh Hunt on Hampstead Heath. WB Yeats, while lodging opposite Christ Church College, Oxford, conceived the shiver-inducing “All Souls’ Night”.

Writers, poets and artists have often gravitated towards the periphery of landmarks, creating pockets of literary and artistic activity. Soho and Bloomsbury are patterned with blue plaques including those for Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley. The pair spent many hours together a couple of miles to the north in what is now the St Pancras Old Church Garden, then a graveyard. In the same spot is the “Hardy Tree”, named for the tombstones stacked around its base by a young Thomas Hardy who, working as an architect in the 1860s, was tasked with exhuming numerous graves to make room for the towering new red-brick St Pancras Station building.

Today the former station is home to St Pancras Chambers, one of London’s most desirable addresses, with 67 dazzling apartments way above the bustling Euston Road.

While settling near a landmark might mean getting accustomed to crowds, it is also a way to feel part of a city. Royal Crescent in Bath, the grade I-listed parade of sand-coloured Georgian terraced houses, is one of the city’s main draws, a frequent filming location for Regency-era period dramas as well as home to hundreds of residents. In Bristol, the former hospital site The General — now converted into modish flats — is not only a standalone architectural site but also just minutes from heritage gems such as Redcliffe Caves.

First and foremost, it’s the rarity of such homes that is their primary appeal. “It’s the best Instagram photo you could have,” says Bassatne, of her Albert Hall views. “It’s waking up in the morning and looking out of the window and having that in front of you. Not many people are that lucky.”

Photography: Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; The Print Collector/Getty Images; Knight Frank