By Helen Barrett

Bad guys live in the best houses. Think of the Ben Rose House in Highland Park, the glass-and-steel home of Cameron's abusive father in Ferris Bueller's Day Off. Or the Park family in Parasite: vain, idle, morally bankrupt, sitting around on covetable chairs in their calm, open-plan fortress.

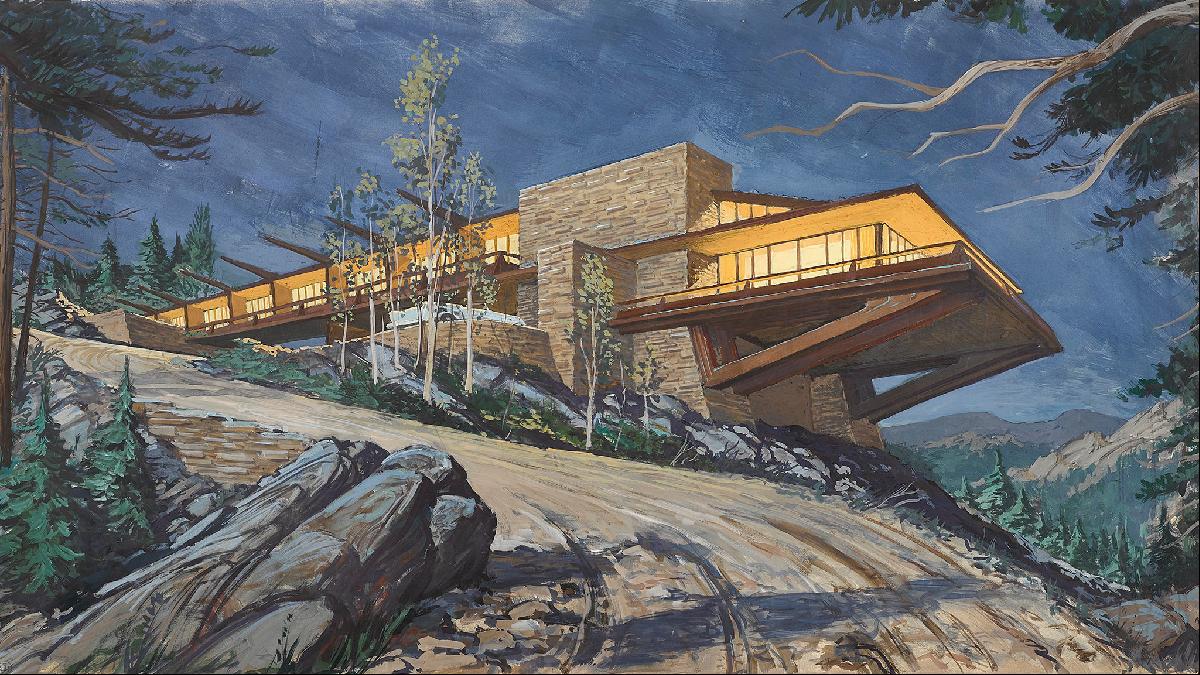

But the best villain in a modernist masterpiece must be Phillip Vandamm, the clenched, cold war enemy of the US, in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1959 thriller North by Northwest. Vandamm lives in decadent, open-plan luxury so rarefied it had to be imagined into existence by Hitchcock’s set designers. Even the house’s location is audacious: Vandamm built his lair on the rocky top of Mount Rushmore.

At the height of the drama, Vandamm — played with chilling charm by James Mason — prowls around his desirable living room plotting his defection with an assortment of sharply dressed henchmen. Meanwhile, his frosty girlfriend/secret agent Eve Kendall, played by the supercool Eva Marie Saint, is forever calling down from the mezzanine, or gazing from the cantilevered rooms at the runway lights (of course, Vandamm House has a private airstrip instead of a front garden).

Meanwhile, all-American hero Roger Thornhill — the permanently bemused Cary Grant — breaks in in an attempt to melt Kendall’s froideur (and save her life). Thrillingly, he does this by clambering up rocks and the angular beams that attach Vandamm House to the mountainside, before intruding — modernist structural detail as plot enabler.

Hitchcock’s preoccupation with architecture and interiors is more than set dressing. As the critic Pete Collard has pointed out, both are so vivid in his films that they start to become supporting characters, channelling the mood of a scene. Vandamm House is desirable and immaculate, but it is also sinister. Likewise, Vandamm uses his surface charm to try to convince Kendall to board his plane — from which he plans to throw her into the sea. “I too believe in neatness,” he tells his adjutant. Evidently.

It is also a house of deception. Everything appears to be calm, but beneath the surface its inhabitants’ intentions are murderous. No one in Vandamm House tells the truth except Thornhill — and he is an intruder. That in itself is ironic, because Vandamm House is an illusion.

Hitchcock tried to persuade the American modernist architect Frank Lloyd Wright to build Vandamm House, but Wright demanded 10 per cent of the film’s total budget as his fee. So Hitchcock turned to set designer Robert F Boyle to construct some of the facade, while the interiors were studio sets. Exterior longshots were matte paintings. A concept painting (main image, above) by an MGM artist was sold at auction by Bonhams in Los Angeles for $4,075, in 2019.

The set design team did such a convincing job that one Australian architect tried to make this house-of-the-imagination a reality. Bruce Rickard designed Mirrabooka House in Castle Hill, New South Wales in 1961 — a fair copy, though it lacks cantilevered drama.

Like many Brits, I grew up in tatty Victorian houses in the 1970s and 80s. My parents were forever “doing up the house” — no one “renovated” in those days — and they were draughty, chilly and dark places. I may have been surrounded by decorative tiling but I envied my friends who lived in quiet, warm, uncluttered modernist bungalows. Everything seemed so calm and civilised. And, as far as I know, the grown-ups in these houses were not intent on world domination.

This ocean-facing house in Maroubra, Sydney, may not have mid-century credentials (it was built in 2004), but, like Vandamm House, the five-bedroom property rises out of a rocky promontory and features panoramic windows for gazing out of. And, on the market for A$20mn ($14.3mn), unlike Vandamm House, it does exist.

But if I really want to reclaim a little of the evil-villain glamour of Vandamm House, I am going to have to buy this 12-bedroom dream home in Los Angeles, on the market for $139mn. It has its own nightclub, vodka tasting room, outside cinema — and even a rock-climbing wall. Which would enable Cary Grant to get in some practice.

Photography: Bonhams; Entertainment Pictures/Alamy; Allstar Picture Library/Alamy; Sydney Sotheby's International Realty; Savills