By Rebecca May Johnson

To write about cooking, I often have to not cook. During periods of intense activity on my book, I ate frozen pizza or ordered falafel, or my partner cooked for me. He too had a job and was also writing a book, and there were many times when neither of us wanted to cook.

It isn’t really possible to cook while doing something else, especially since the forms of cooking that might allow this — slow cooking in the oven or on the stove — have become a wild extravagance due to fuel prices. Even then, cooking involves planning, going to shops, unpacking and putting away, disposing of packaging and scraps, monitoring freshness, cleaning the fridge or the kitchen, taking out the bins and so forth. All of this work, for that’s what it is, is profoundly inefficient in terms of energy, wasted produce and labour when performed by individuals at home.

My fantasy home is born out of this situation: it is a place where domestic work such as cooking is mostly performed collectively — reducing the burden on people’s time and making for better use of energy and produce, while also being far more sociable.

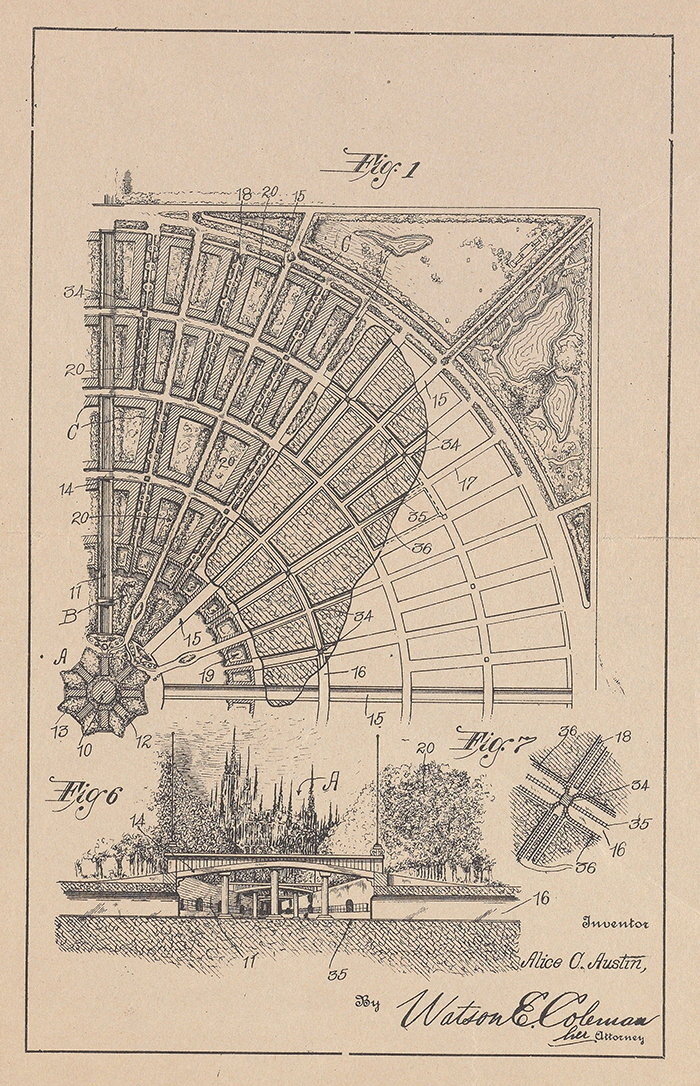

I first read the term “kitchenless city” in MOLD magazine last year. I was intrigued and went on to read Dolores Hayden’s 1978 essay “Two Utopian Feminists and Their Campaigns for Kitchenless Houses”, which explores various visions for kitchenless living in the 19th and early 20th century. Hayden’s description of the 1915 plan for Alice Constance Austin’s utopian Llano del Rio commune, in California, really caught my imagination.

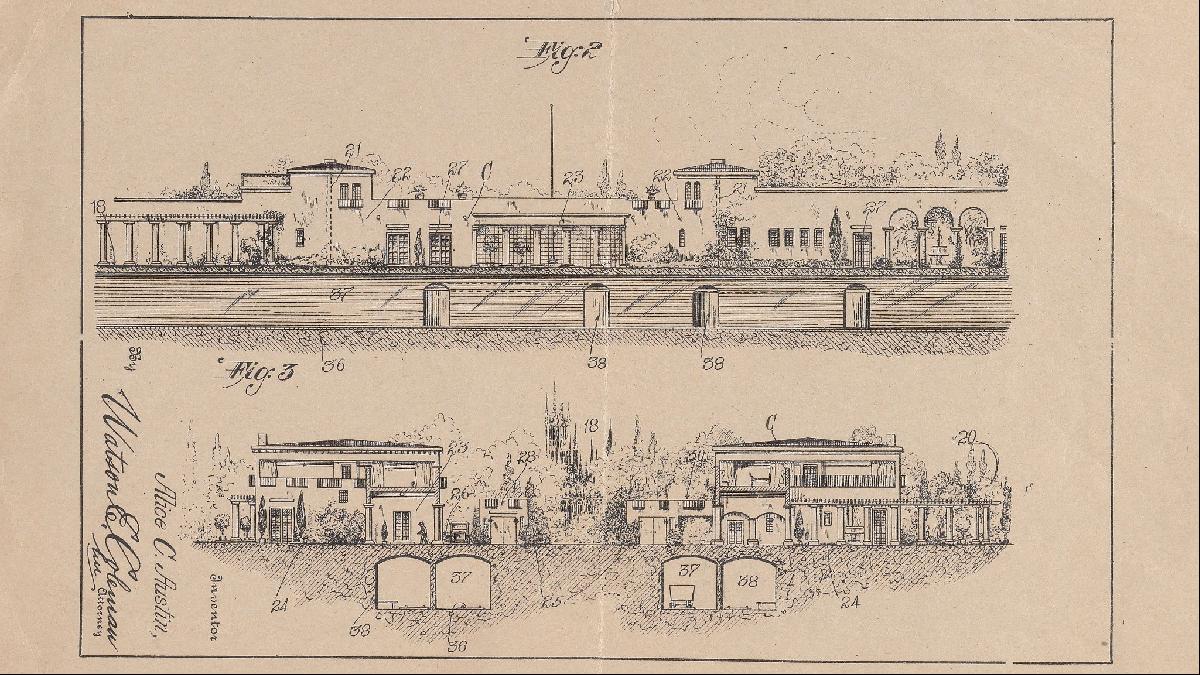

It feels like something from a sci-fi novel: "Each kitchenless house is connected to the central kitchen through a network of tunnels. Railway cars from the centre of the city bring cooked food, laundry and other deliveries to connection points, or “hubs”, from which small electric carts can be dispatched to the basement of each house."

My fantasy home requires the building of a city to Austin’s design. I would cook one day a week in the large, centralised kitchen alongside other residents while catching up on gossip and news. Menus would change depending on who was in the kitchen that day and what was in season. At other times, I would receive my meal along with freshly laundered clothes via the underground tunnel and read and write, liberated from the “double shift”, the term used to describe how a day of paid labour is often followed by an evening of unpaid domestic work.

There is, of course, a dystopian version of my fantasy: a city where everyone stays at home and orders food that has been prepared in dark kitchens on the outskirts of the city by poorly paid workers. For me, it is fundamental that everyone does some share of the work and can thereby understand and value it — and, crucially, no one would have to do it every day. Austin (on the left in the main image, top), does not relegate her collective kitchen to the edge of the city, it is placed at its centre, which I could walk to via leafy streets, unbothered by traffic.

The houses that Austin designed for her kitchenless city are minimal and still feel modern a century later. Rooms are organised around a central courtyard. As Hayden describes, Austin thought hard about how to reduce the work of housekeeping, providing “built-in furniture and rollaway beds to eliminate dusting and sweeping in difficult spots, heated tile floors to replace dusty carpets and windows with decorated frames to do away with what she called that ‘household scourge’, the curtain.” To that, I might add an induction hob and an oven for the times when — relieved of so much domestic work — I feel like cooking for fun.

Rebecca May Johnson’s memoir, ‘Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen’, is published by Pushkin Press

Photography: Courtesy of Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library