By Anna Winston

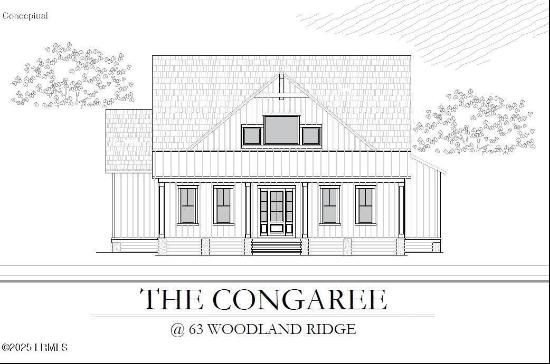

The Marmoripalatsi or Marble Palace is an idiosyncratic building by a pioneering architect. For over a century, the palace, which is clad in heavy blocks of grey Förby marble, has sat on the edge of Helsinki’s Kaivopuisto park as a monument to the city’s affluence at the beginning of the 20th century. Thanks to an extensive renovation by SARC Architects, which has seen the building transformed into four new residences, it is now part of the city’s future.

The building was designed in 1916 by Eliel Saarinen, a prominent Finnish architect who played a central role in planning modern Helsinki. Saarinen had made his name with major structures in the capital including its railway station and the Finnish National Museum, and the Marble Palace is a rare residential work by the architect.

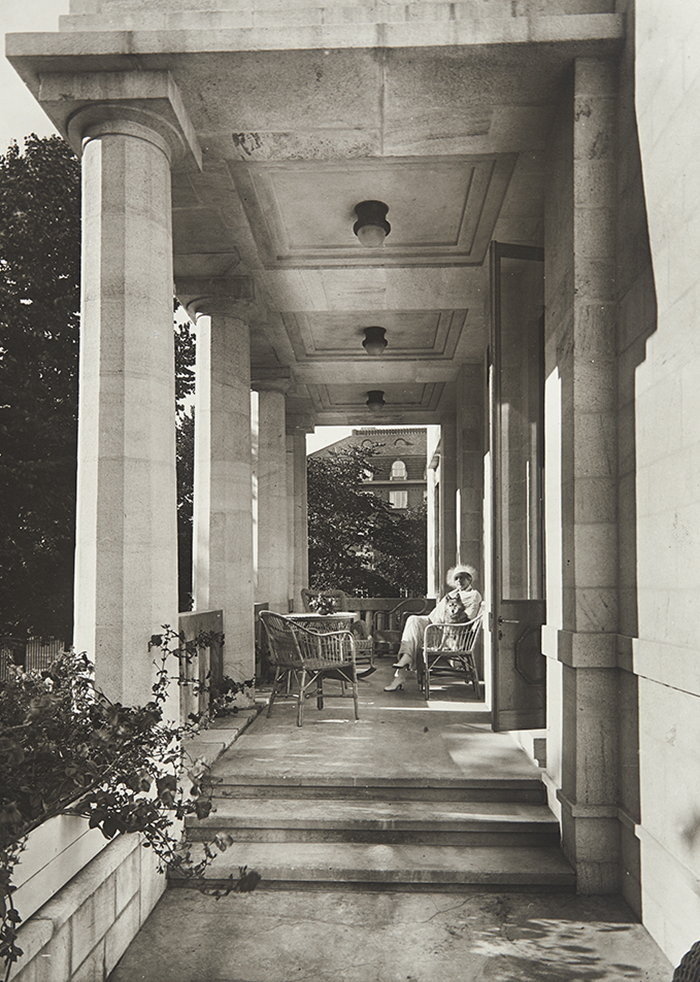

Commissioned by industrialist August Keirkner and his wife Lydia, the house was intended to host important guests and the couple’s impressive art collection to equal effect. Keirkner died before the house was completed in 1918, and shortly afterwards Saarinen moved to the US where he would inspire a generation of Modernist architects and designers including Harry Bertoia, Florence Knoll, Saarinen’s son Eero and Charles and Ray Eames.

In the 1930s, Lydia Keirkner sold the house to another industrialist, Rudolf Walden, who lived there with his family until his death in 1946. The property then fell into the hands of the state and was used as a courthouse. In some ways this helped preserve it: many of its original features were kept intact or simply boarded over. But the change of use presented some challenges when it came to restoring and renovating the building, which is protected and listed, for contemporary residential use.

“After more than 70 years serving as a courthouse, it was not a home,” says Sarlotta Narjus, chief executive of SARC and lead architect on the project. “There were no kitchens or bathrooms, but the first floor was in pretty good shape. We had the wallpaper, the flooring, the old fireplaces.” And as well as the original wooden panelling, the windows and the exterior were more or less untouched.

The house had been designed with every modern luxury, including apartments for the Keirkners’ driver and staff, and lush views over the park. Since its conversion to use as a courthouse, many of the less impressive rooms had been used as storage spaces or to host services such as heating and ventilation. The attic and much of the ground floor was largely unused. These spaces were a boon for the architects, who were able to add modern facilities and divide the space into four apartments without having to add an extension.

The largest apartment, at 615 square metres, occupies most of the Keirkners’ original residence: a unique one-bedroom space with some of the property’s most stately rooms, currently on the market for €15.39mn. A more modest three-bedroom attic flat, priced at €12.66mn, is the most modern of the new residences but still manages to capture the spirit of the original space thanks to carefully chosen materials and fittings. All apartments have patios, terraces, a winter garden or balconies, and there are views over the park from the rear.

Alongside the restoration of the original interior, new features have been included to bring the building up to date, including LED lighting and a new elevator and staircase. Bright, white marble bathrooms are a nod to the building’s name, even if the original distinctive grey marble from the Finnish archipelago can no longer be sourced.

“There’s a harmony with the original architecture,” says Narjus. “I like working with old buildings — it’s always interesting to see how you can keep the soul of the building and not destroy it. That’s what was important here.”

Photography: Paasikivi/Wikipedia; Eric Sundström, Helsinki City Museum; Ari Saarto/Finnish Heritage Agency; © Tietoa Finland Oy/Tom Kraappa