By Chris Hayes

The Hungarian-born Marcel Breuer was one of the youngest students at the influential German design school, the Bauhaus. During this period, he created the Wassily Chair, which quickly became a hit — and is now regarded as one of the most iconic furniture designs of the 20th century. But architecture would soon become his driving ambition, resulting in weighty contributions to Modernist architecture.

Relatively unsuccessful attempts to establish himself as an architect in Germany preceded his need to flee the country after the Nazis came to power. Despite initially dragging his heels, he eventually followed Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, finding refuge in London in 1935. Yet his forward-looking thinking can be found in the few early commissions he managed to secure, such as the Harnischmacher house in Wiesbaden and Doldertal apartments in Zurich, alongside a number of theoretical drawings for houses, hospitals and highways.

Everything changed when he followed Gropius again, relocating to Harvard in 1937. Breuer joined the faculty of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, with Gropius as chairman; their students, among them Philip Johnson, IM Pei and Paul Rudolph, would change American architecture forever. Breuer and Gropius collaborated on a series of homes for fellow Harvard professors, using these commissions to test new ideas. Breuer’s distinctive approach to residential design would come to fruition in 1945 with Geller I, where he divided sleeping and living between separate wings in what he termed a binuclear layout.

An installation of this design at MoMA in 1949 sparked a flurry of interest — and a series of residential commissions. While the original Geller I was controversially demolished by its owners (to expand their tennis court), countless examples of his innovative approach can be found across the US and Europe, such as 204 Cleveland Drive in Croton-on-Hudson, New York state (main image, top). Completed in 1950, the single-storey open-plan home is classic Breuer: bedrooms and living space flow from a central entrance, while a gently slanting roof, locally sourced stone and other material choices create a softer version of Breuer’s characteristic hard-edged “international style”. Around the same time, in 1948 and later in 1952, he would build two houses of a similar style for himself in Connecticut.

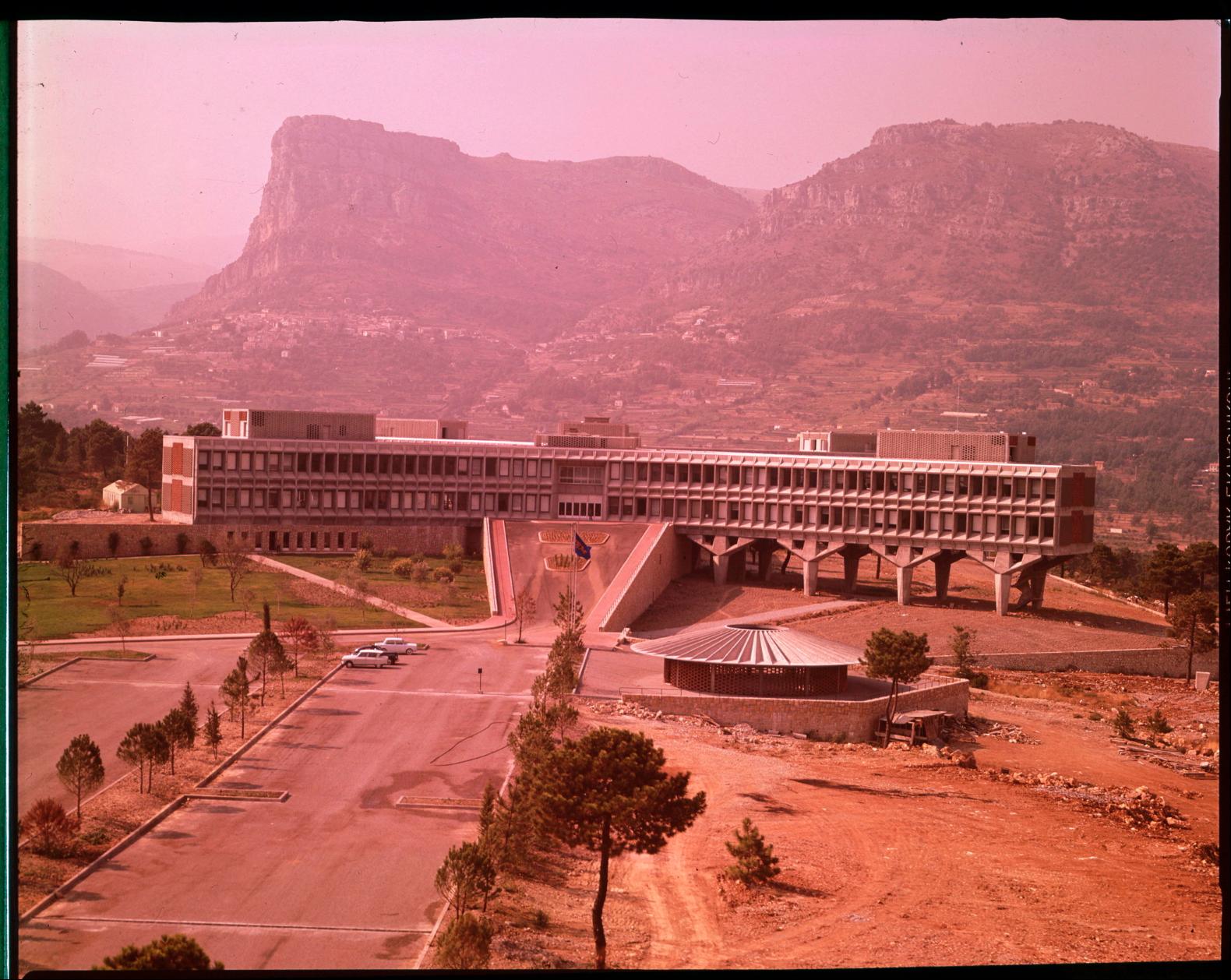

The 1950s and 1960s were some of Breuer’s most productive years. Institutional commissions flowed — as did tonnes of concrete, his favoured material during the later half of his life. Contrasting the lightweight design vocabulary of his residential projects, he created gigantic Brutalist buildings with modular prefabricated concrete panel facades, most strikingly at the IBM Research Centre in Alpes Maritimes, southern France and the Department of Housing and Urban Development in Washington (a former secretary of HUD, Jack Kemp, once described the building as “10 floors of basement”). Notable, too, was his hiring of Beverly Lorraine Greene in 1955, the first African-American woman architect in the US, who worked on major projects such as the Grosse Pointe Public Library.

At the peak of his career in 1968, the American Institute of Architects awarded him with the prestigious Gold Medal; his acceptance speech celebrated architecture that was “anchored in usefulness”. But a controversy arose the same year in response to his design for a 830-ft skyscraper atop Grand Central Terminal. An ensuing legal case blocked the project and reached the Supreme Court, setting a precedent used by other cities since. He lost friends and the favour of many critics.

Today, the critical consensus on Breuer is one of appreciation, as seen by the colloquial references to “Breuer buildings” and numerous campaigns to prevent the demolition of his work, such as a fundraising campaign launched by Cape Cod Modern House Trust in 2023. His ability to create architecture that speaks to the moment — while possessing a timeless sculptural flair — is as attractive as ever.

Photography: Dot Record Media/Julia B Fee Sotheby’s International Realty; permission of Lother Versi; Getty Images