By Samir Chadha

As the US’s most renowned architect, Frank Lloyd Wright’s influence and body of work extends to almost every aspect of the built environment. While his most visited building is likely the Guggenheim in New York, it’s his domestic work that he thought and wrote about extensively — an attempt to propose an alternative to stacked city life.

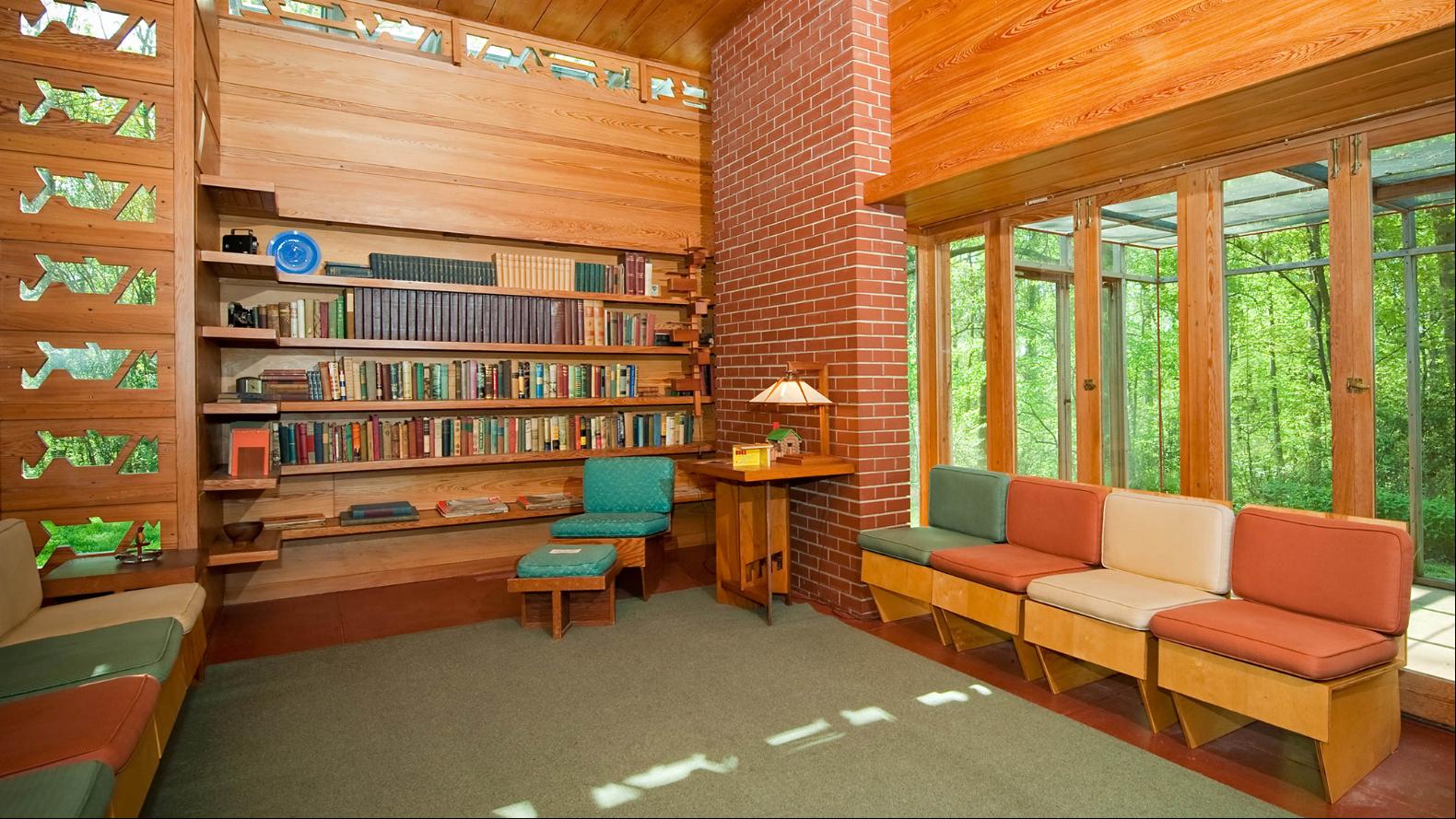

His most well-known domestic project, Fallingwater, is the grandest entry into that canon. Perched above a waterfall, it exemplifies his principles of “organic architecture” — broadly aimed at bringing the built and the natural closer together. From afar, its forms are a continuation of those around it but Wright would have preferred it to sit lower, beneath the falls, so as not to overshadow that landscape. His “Usonian” houses sit at the other end of his legacy — homes that were simple, and therefore affordable, but still thoughtfully designed, with details tailored to individual inhabitants (main image, top). The most radically realised example of that vision sits in upstate New York; an initially cooperatively owned cluster of 47 homes all either directly designed or approved by Wright himself.

There are glimmers of that domestic vision in his early domestic work — so-called Prairie homes designed in the late 19th and early 20th century. The first of those was a house for WH Winslow in River Forest, Illinois, on sale with @properties, an affiliate of Christie's International Real Estate. Pitched low and broad, like the midwest landscape around it, it is straightforward geometrically and stretched out laterally — ideas Wright would continue to push throughout his career. That symmetrical front gives way to a complex, conglomerate rear — decorative mores that complement the garden, but don’t impose themselves on a broader public. Having said that, the design was so avant-garde at the time that Winslow allegedly avoided commuting by train for months after moving in, to avoid being teased about it.

As much as he loved nature, Wright’s homes weren’t looking to resemble it. He wrote, of “imitative eclecticism”, that, “At best it can be no more than some exploitation of something ready-made. At worst it is a kind of thievery.” His forms, then, worked to frame and complement that existing space — materiality might borrow from the surroundings, but his stark, clean lines are unmistakably man-made. That might be the element of his influence that fully permeated modern building, as the architecture of the 20th century tended, largely, to move away from decoration and towards either a high-tech sleekness or brutalist efficiency.

While Wright wanted his homes to be practical, and not to get in the way of nature, that wasn’t to say they couldn’t be beautiful. Projects such as the Warren Hickox house in Kankakee, Illinois (also listed with @properties), weren’t quite so grand — there’s less classical influence in the form of arches, friezes and golden bricks — but still managed to retain the balance of ornament and function. The beams and other architectural features inside resemble Tudor houses, but also evoke the nearby trees, again, blurring the gap between inside and out. The distinctive roofs nod to Japanese styles, but balance protection from the rain with a path for sunlight.

In his writing and public speaking, Wright regularly lamented the alienation that came from the forms of city living and working he saw in the US. In 1932, in The Disappearing City, Wright asked, “But why try to make buildings look as hard as machines? That means that life is as hard as machines, too.” His vision of the future would instead be made up of individually considered domestic spaces — each of them a little bulwark against modern isolation.

Photography: The Washington Post/Getty Images; Richard T Nowitz/Getty Images; Arcaid Images/Alamy Stock Photo; Real Vision Photography